Hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid was steered to New Jersey’s largest charter school management companies over the last decade, helping them to create a network of school buildings that are privately owned.

In other parts of the country, the same aid programs provided interest-free loans to both traditional public schools and charters to construct and renovate buildings. But a much different model emerged in New Jersey as Gov. Chris Christie’s administration gave the state’s entire share of the federal aid — bonds worth more than a half-billion dollars — to charters and other non-traditional public schools.

More than three-quarters of that money was awarded to the state’s two largest charter school operators, KIPP New Jersey and Uncommon Schools, which used it in ways that strayed far from the intent of the aid programs.

The companies fashioned complex financial structures that allow them to exploit the bonds by tapping into the aid as a steady stream of income over decades, using methods that in some cases have drawn the scrutiny of federal investigators.

“What I am concerned about is public money going into buildings that are privately owned. If we have public dollars going toward what’s supposed to be a public school but owned by a private corporation, that’s not acceptable.”

The result is a string of school buildings that were built with taxpayer money but remain in private hands. The companies that own them were created to purchase real estate and renovate buildings for charter schools, but they are kept legally separate from the charter schools that send millions of dollars their way each year in rent.

Charter schools rent these buildings indefinitely. Leases do not contemplate a time when rent payments would end or when the buildings would be turned over to the public charter schools, even after the debt is paid.

The deals involve related companies that are created to lend money to one another — an arrangement that is not uncommon in the world of private finance. But in this case the arrangements steer tax dollars — federal aid that subsidizes the projects by covering the interest on the loans — to private groups that don’t have to share details with the public or the state about how they use the cash. Charter school operators have said they resort to unusual, complex financing arrangements because the state doesn’t provide funding for their facilities, and because they are barred from using public money other than federal dollars for construction.

Officials from KIPP New Jersey and Uncommon Schools declined to be interviewed about those deals or the ownership of the buildings that their schools use.

“In my experience that isn’t the way it’s supposed to be done. You have to give them credit for being clever. I assume they have an attorney who says it’s legal.”

Richard Bozza, executive director of the New Jersey Association of School Administrators, said he’s long heard charter advocates talk about the difficulty of funding facilities.

“What I am concerned about is public money going into buildings that are privately owned,” he said. “If we have public dollars going toward what’s supposed to be a public school but owned by a private corporation, that’s not acceptable.”

Art Stellar, vice president of the National Education Foundation, an early proponent of the federal construction aid programs, said charters and traditional public schools typically use the federal bonds as interest-free loans. He said he’s never seen them used as they have been in New Jersey — with charter school support groups collecting the interest payments themselves.

“In my experience that isn’t the way it’s supposed to be done,” Stellar said. “You have to give them credit for being clever. I assume they have an attorney who says it’s legal.”

Charter operators said their financial transactions are reviewed by attorneys to make sure they are legal and “arms-length” — meaning that the various parties in the transactions acted independently.

Officials with the Economic Development Authority, the state agency that has issued more than $800 million in bonds to finance the purchase or construction of charter school buildings in New Jersey, said its bond counsels review the transactions to ensure they follow federal tax rules.

But the officials acknowledged that the authority doesn’t examine some details, such as who owns the buildings that the bonds are funding, because state money isn’t involved. The agency calls itself a “conduit issuer” of bonds in charter school deals; it issues bonds to be purchased by investors — in some cases charter school support groups — but has no other role in the transaction.

Meanwhile, millions of dollars in federal taxpayer money is being moved from one company to another without accountability. It’s not possible to track all the money, because charter support groups are not subject to public records laws.

Here's how the arrangements work: A charter school support group borrows money from banks and uses the cash to purchase the bonds instead of having investors buy them, as is typical in most bond sales.

The group then lends the money it used to purchase the bonds to another group with ties to the charter school. In some cases, the money funds a school project. In others, it’s used to finance another loan, at interest, to a third charter support group that pays to construct or renovate a building.

Documents show that the federal aid goes toward repaying the bank loans that were taken out to purchase the bonds in the first place. Any shortfall is covered by the public charter school's rent, which is provided by state and local taxpayers.

NorthJersey.com and the USA TODAY NETWORK New Jersey examined tens of thousands of pages of bond documents, leases and business filings related to more than a dozen federal bond transactions.

Among the findings:

- The federal government does not require school buildings funded with the bonds to be publicly owned. The IRS said cash from the bond sales isn’t supposed to go to for-profit companies, but that happened in one New Jersey deal. State officials said it’s allowed if the building is a public school, no matter who owns it.

- One of the largest charter operators was allowed to wait five years before spending millions of dollars from one bond issue. Yet state officials said they funneled the aid to large groups because they had shovel-ready projects and could use it immediately.

- There are close relationships among the private companies involved in the deals. In one case, an executive in a charter management company was also the president of a firm that was paid to serve as the financial adviser on a building project for the school. She also was an officer with three other companies involved in the same deal: one that lent money, one that borrowed it and another that owns the property.

- Charter operators have been able to maximize the amount of federal interest payments the support groups receive each year, and there is nothing in the law to stop them. The principal is due in a lump sum when the bonds are retired, so the annual interest payments never go down. In typical bond transactions, interest payments decrease as the principal is paid down.

- The IRS has launched a review of one charter school support group’s purchase of federal bonds at a deep discount — a technique that allowed the group to receive as much aid as it would have if it had paid full price. It’s unclear whether the subsidies — a chief source of income for the group — are in jeopardy. Support groups for at least two other charter schools have struck similar arrangements.

Julia Sass Rubin, who teaches at Rutgers University and specializes in education policy, said the charter school operators appeared to be “dealing with themselves” to get the most out of the subsidies, with the money staying within “their friendly circle.”

Federal aid from the bonds underpins Newark’s largest charter school projects, with a total of $120 million in interest payments slated to be paid over decades to private companies for three of the newest buildings: Uncommon Schools’ recently opened six-story school on Washington Street; a KIPP New Jersey high school on Littleton Avenue; and a Marion P. Thomas Charter School building on Sussex Avenue.

KIPP New Jersey is paid to run the TEAM Academy Charter School, and Uncommon Schools is paid to run the North Star Academy Charter School. The two nonprofit organizations receive millions of dollars in management fees from the schools.

Most of the bonds were part of a program created by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Known as Qualified School Construction Bonds, they provide federal tax credits or direct payments to the bond-holder. Most of the transactions reviewed for this story involved direct payments.

The federal government designated $439 million of the bonds for use by New Jersey.

The Christie administration set them all aside for charters and other non-traditional public schools.

The federal government gave another $53 million of the bonds to the Newark school district, but they were all directed to a limited group of charters with the blessing of school and city officials, including Cory Booker, Newark’s mayor at the time and now a U.S. senator and Democratic presidential candidate.

Over the past nine years, the state gave KIPP and Uncommon an additional $95 million in federal bonds that were part of a separate program created in 1997 to renovate schools.

The federal aid programs, which were still being used as recently as late 2017, have since been discontinued, but taxpayers will continue paying interest on the existing loans for decades.

KIPP, Uncommon and Marion P. Thomas declined to answer most of the questions that were put to them in writing, but they issued statements saying their private support groups help them reduce costs and free up resources for students. They declined to discuss financing details.

The state provides no startup or facilities funding for charter schools and limits the debt such schools can carry. Those rules, experts say, encourage charters to use private groups to own their buildings and to enter into complex deals that involve loans between related companies that are set up to support the schools.

Dwight Berg, a financial adviser on some KIPP New Jersey deals, said in telephone interviews and emails that state law and regulations have made it difficult for charter schools to own their facilities. The state bars them from having long-term debt that exceeds the value of the property and from entering into deals that allow lenders to go after other assets if they default on loans.

“That can be a problem,” Berg said, adding that New Jersey places more restrictions on charters than some other states do, pushing them to lease buildings.

Berg and his company were part of at least eight deals using the federal subsidies for projects in Newark — six for KIPP and one each for Uncommon and Marion P. Thomas. He said he could not discuss the transactions in which he was involved.

“Part of the goal was to try to find projects ready to go that could hit the ground as quickly as possible."

KIPP and Uncommon received a total of $400 million in the federal bonds for charter school projects in Newark and for so-called "renaissance schools" in Camden. Unlike charter schools, renaissance schools are approved by the local district and are allowed to use state funds to construct new buildings. They also receive more funding.

In Newark alone, private companies created to support KIPP and Uncommon charters are scheduled to receive federal subsidies valued at more than $200 million from a dozen deals related to the construction and renovation of buildings.

A group formed to support Marion P. Thomas will receive $31 million in subsidies from one deal.

A former head of the state Economic Development Authority said the agency followed directions from state officials during the Christie administration in issuing the federal bonds for charter school projects. KIPP and Uncommon got the largest shares of the subsidies, he said, because they’re “big operators” with “projects in the works.”

“Part of the goal was to try to find projects ready to go that could hit the ground as quickly as possible,” said Timothy Lizura, the agency’s president and chief operating officer until July 2018.

However, in available documents, the same projects often were listed in multiple applications for financing, and it wasn’t always clear when the money was spent. In one case, Uncommon Schools was permitted to use money from a $7.8 million bond issue five years later. Typically, the money is required to be spent within three years.

The authority said the IRS granted a two-year extension because Uncommon, which did not respond to questions about the delay, was not able to purchase property that had been slated to be part of the project. Five years after the bonds were issued, the authority said, Uncommon spent the money on another building.

Newark passes $53 million in federal bonds to charters

Newark’s school district, the state’s largest, got $53 million in bonds from the federal government, but most of it, $38 million, went to KIPP and Uncommon for two projects. Another $13 million was used to build a complex in Newark known as Teachers Village that includes charter schools and housing for teachers.

And a little more than $2 million of the bond money was designated for the Adelaide L. Sanford Charter School, which the state closed almost six years ago.

An investigation by the Education Department’s Office of Fiscal Accountability and Compliance determined that Adelaide Sanford’s CEO had a conflict because she was also the executive director of the school’s landlord. It found that “the charter school’s lease was used to secure” the landlord’s repayment of more than $8.2 million in loans, including the federal bonds, and that at one point the school paid to rent a building it didn’t use.

“Since the federal financing made available would have been lost to Newark if not issued, the decision was made by multiple government agencies to ensure it went towards strengthening our public-school system, supporting Newark students, and providing our children the tools they need to reach their highest potential.”

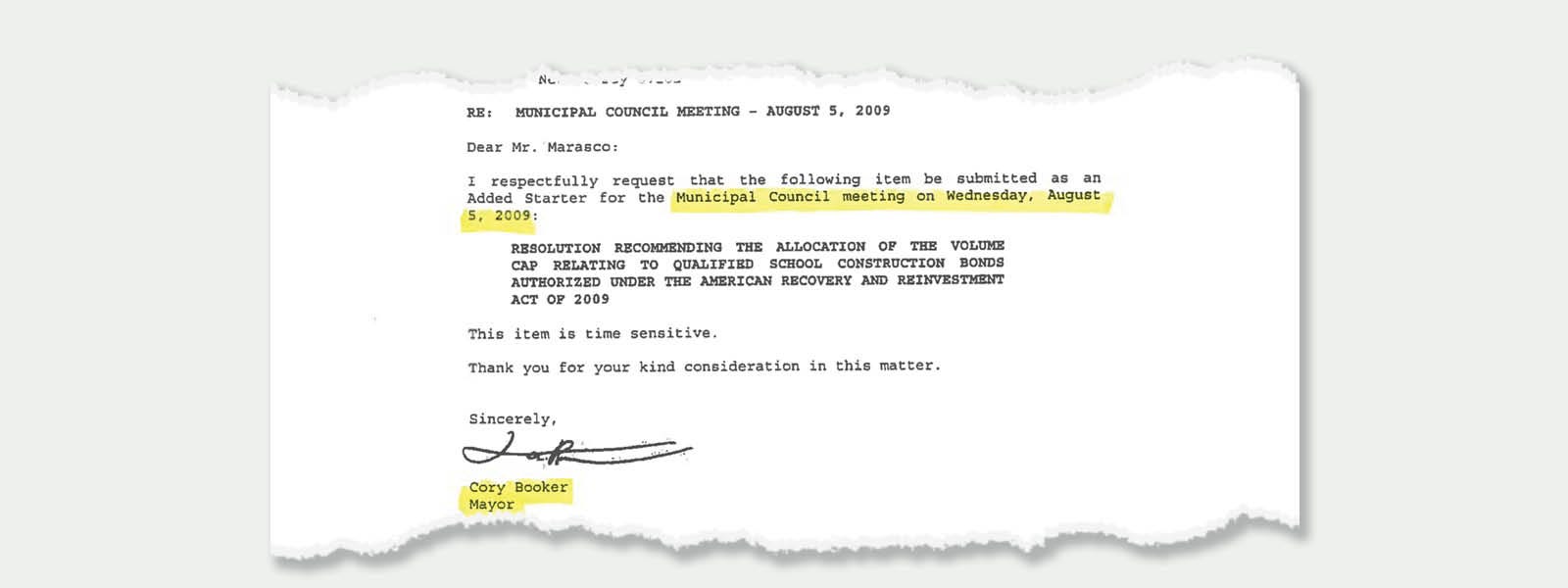

In 2009, when he was Newark’s mayor, Booker asked the City Council to consider a resolution recommending that bonds meant for the city’s school district be used by charter schools. The council passed the resolution, and school district officials eventually transferred all the bonds to charters.

Booker declined to be interviewed. He said in a statement that the transfers were spurred by fears that Newark would miss out on the federal funding if the bonds weren’t issued within a certain period of time.

“Since the federal financing made available would have been lost to Newark if not issued, the decision was made by multiple government agencies to ensure it went towards strengthening our public-school system, supporting Newark students, and providing our children the tools they need to reach their highest potential,” Booker said in the statement.

A state report from 2012 said large school districts would have to forfeit the federal bonds to the state if it didn’t use them in a timely fashion. But federal law does not say they would have to forfeit the bonds under those circumstances.

Big discounts mean more income for private groups

The big charter operators in New Jersey made the most of the federal bonds by giving themselves deep discounts on the purchase price, often more than 30 percent — a practice that is now being scrutinized by the IRS.

Lizura, the former Economic Development Authority president, said his agency had nothing to do with the discounts; they were set by the bond buyers and the borrowers. In more than a dozen transactions involving charter school buildings in Newark, that meant the schools’ support groups, which were on both sides of the deals, controlled the prices.

“The disclosure of such records would be detrimental to the public interest."

That’s how private groups related to KIPP and Uncommon Schools managed to pay a total of just $159 million to purchase bonds with a combined face value of $232 million.

However, the annual interest picked up by taxpayers is based on the full price of the bonds. As a result, taxpayers will end up paying millions more than they would have paid based on the actual purchase price.

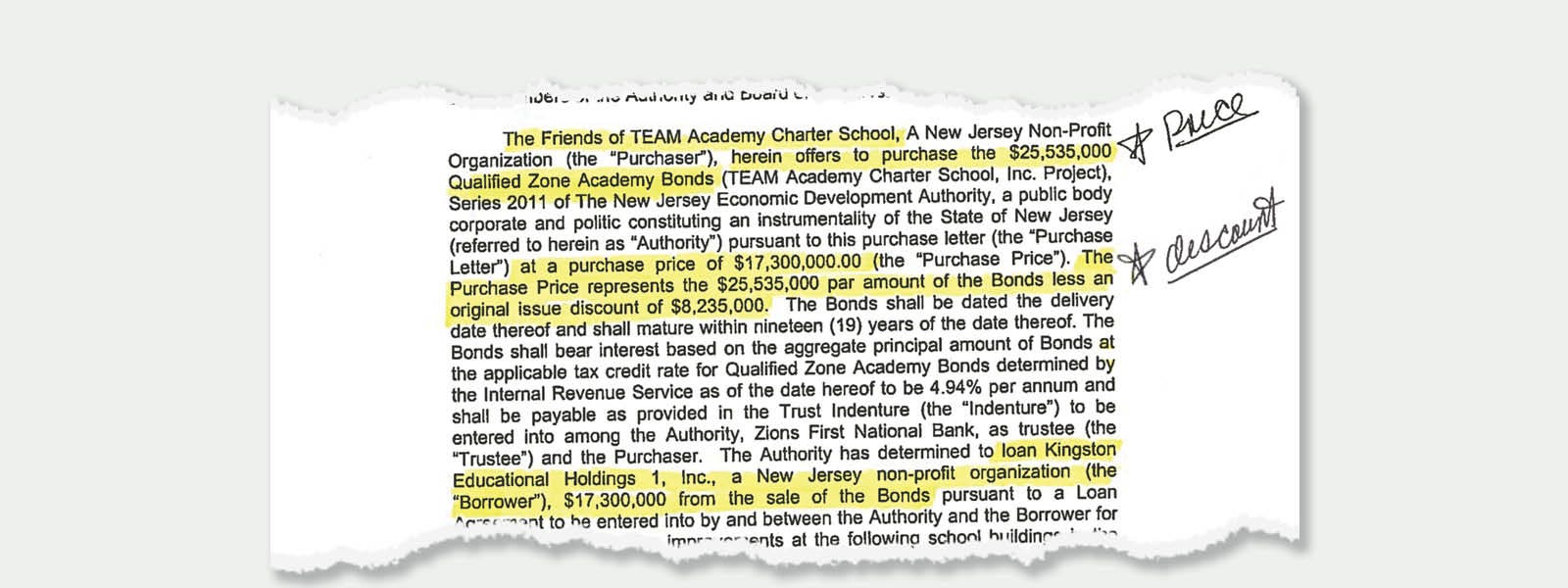

The IRS has been examining the discounts taken by the Friends of TEAM, a private group created to support Newark’s TEAM Academy Charter School in real estate transactions. TEAM is run by KIPP New Jersey.

In one transaction that is under review, the Friends came to an agreement with a related company called Kingston Educational Holdings to pay $17 million for bonds that had a face value of $25 million.

The Friends lent cash from the sale to Kingston.

The federal government is paying annual interest to the Friends based on the higher amount — a total of almost $24 million over two decades.

TEAM Academy officials denied a public records request for documents related to the IRS review, saying they are related to an “investigation in progress by a government agency.”

“The disclosure of such records would be detrimental to the public interest,” Steve Small, KIPP New Jersey’s chief financial officer, wrote in an email.

The Friends group acknowledged in bond documents that the investigation has the potential to lead to a loss in revenue, writing in a financial report that its “bond investments will be adjusted by the estimated loss” if its revenues decline as a result of the IRS review.

The documents didn’t specify what kind of adjustments would be made.

The bonds being reviewed are tied to millions of dollars in federal subsidies paid to the Friends each year, allowing the group to repay bank loans that had been taken out to purchase the bonds.

The Friends wrote in the report that its attorneys advised that “the bonds comply with applicable tax law” and that the federal subsidies have been “appropriate and correctly calculated.”

Kingston ― the related company that received loans from three of the sets of bonds under review ― “will continue to refute any argument by the IRS to the contrary,” the Friends wrote in the report.

While the investigation was underway, the state Economic Development Authority issued $46 million in bonds last year to refinance some of the Friends’ bank loans, including at least three of those being reviewed. The authority declined to discuss the IRS investigation and did not provide records related to it. The IRS did not respond to a records request.

“This is pending,” Erin Gold, the authority’s chief of staff, wrote in an email. “The discounts are not in EDA’s purview; that is between the lender and the borrower — the price at which the bondholder bought the bond. As a conduit, the EDA appropriately relies on bond counsel.

“This is not just NJ,” she added, referring to the discounts. “This is how transactions were handled across the nation.”

The Friends were not the only group in the state to use the discounts. They were part of a dozen projects involving KIPP New Jersey, Uncommon Schools and the Friends of Marion P. Thomas Charter School in Newark over the last decade.

“This is pending. The discounts are not in EDA’s purview; that is between the lender and the borrower — the price at which the bondholder bought the bond. As a conduit, the EDA appropriately relies on bond counsel. This is not just NJ. This is how transactions were handled across the nation.”

In declining a request for records related to the IRS reviews, the EDA said it is in possession of IRS notices related to 10 sets of federal bonds issued for charter school projects in Newark.

Five were related to TEAM, four to Uncommon and one to Marion P. Thomas.

One routine review related to TEAM was closed, according to a financial report. No other information about that was available.

Lizura said the deep discounts were “unique to this program” and made up for the relatively low interest rates set by the federal government, in some cases below 5 percent. Since the borrower is supposed to repay the face value of the bonds, not the lower sales price, it would owe millions of dollars more than it borrowed, effectively making up for the low interest rate.

Because the groups involved in the deals are part of the same organization, they essentially owe the money to themselves, raising questions about how the debt would ultimately be repaid.

Though the loans have been extended between related companies, IRS rules require them to be repaid — but not necessarily in cash.

Big debts — but only on paper

The big charter operators face hundreds of millions of dollars in debt on some of their buildings — at least on paper. Most of the loans are scheduled to be repaid in lump sums years from now.

The Friends of TEAM said in a 2017 financial statement that it is owed more than $125 million in principal from the purchase of five sets of bonds whose combined sale price was $85 million. The debt, which is owed by companies that tax documents indicate are related to one another, “may require a sale or refinance of the underlying financed properties,” the statement said.

However, in at least one case the debt is scheduled to be repaid not with cash but rather by shifting the ownership of a school building from one support group to another, leaving it in private hands after the public has paid for it.

Documents show that a KIPP building on Norfolk Street in Newark is scheduled to be given to the Friends of TEAM eight years from now to satisfy a $28 million debt related to two sets of federal bonds. It’s now owned by another group with ties to TEAM that leases it to the charter school. The deal has unique features that require a government agency to own the building briefly before it’s passed to the Friends.

KIPP New Jersey officials acknowledged in a statement that the Friends plan to take ownership of the building “in lieu of cash repayment” of the debt.

“It’s fine for related parties to loan to each another. The real question ends up being, is it really a debt instrument? The parties expect to be paid. If the intent when starting is, I may get federal subsidies and I’m not going to repay the principal — that’s not a debt instrument.”

Even after the bond debt would be erased by the transfer, the public charter school is scheduled to continue to pay rent of at least $1 million a year, a cost to be borne by taxpayers.

It’s not clear whether the transfer of buildings would be a model for other charter school projects funded with the help of federal aid. But experts said that simply cancelling the debts would put the charter support groups at risk of losing the federal subsidies because they wouldn’t be considered true loans.

“It’s fine for related parties to loan to each other,” said Charles C. Cardall, the chairman of the tax department at the Orrick law firm in San Francisco. Orrick is a national firm that has represented Gannett. “The real question ends up being, is it really a debt instrument?”

“The parties expect to be paid,” he added. “If the intent when starting is, I may get federal subsidies and I’m not going to repay the principal — that’s not a debt instrument.”

KIPP New Jersey officials said that “no debts are being canceled” and that “the borrower is repaying the debt at maturity” of the bonds, even though it’s owed to a related company.

Berg, the KIPP New Jersey adviser, said debts may be repaid in “cash or kind.” That means they may be repaid with something of value other than cash — like a building.

“Then that lender is not cancelling debt” because the lender is getting “something of value,” Berg said. “That debt would not be considered canceled by the IRS.”

Charter operators declined to comment on their plans.

KIPP New Jersey, Uncommon Schools and Marion P. Thomas all said in statements that their deals had been done at “arm’s length” — a legal term meaning that the various parties in the transactions acted independently.

Yet some of the same people sit on boards or act as officers of both lender and borrower.

Timothy Carden, for example, sits on the Friends of TEAM board, which purchased the federal bonds. He also sits on the board of two companies that received loans from the Friends and owe tens of millions of dollars related to four KIPP buildings. He is the managing director of a financial management company in New York.

Tom Comiskey, one of M&T Bank’s top executives, sat on the Friends of TEAM board until last March. The bank lent tens of millions of dollars to the group over the last decade. Late last year, a subsidiary, M&T Securities, sold bonds that were used to refinance those loans and others, getting a fee of $300,000 for its services while helping the bank recoup its investment.

A bank spokesman said in a statement that Comiskey recused himself from discussions related to transactions with M&T while he was a member of the Friends board. The spokesman, Chet Bridger, also said M&T “has a long relationship with KIPP New Jersey” and was selected “as the winning bidder” to sell the bonds used in the refinancing.

Richard Vieser, a bank executive, was president of the Friends of Marion P. Thomas board when it purchased $35 million of the federal bonds. He is now the vice president of the Friends board and is also listed as vice president of a company that received a loan from the proceeds of the bonds and owns the charter school’s Sussex Avenue high school.

Diane Flynn was Uncommon Schools’ CFO and also headed a financial firm that advised Uncommon on at least six projects, including a $69 million, six-story school that recently opened on Washington Street in Newark. She was listed in state business filings for 2017 as a principal officer in two companies involved in the deal — one of which lent money to the other. Flynn also was CEO of another company that owns the building and leases it to the charter school.

None of them would comment for this story.

Barbara Martinez, an Uncommon Schools spokeswoman, wrote in an email that Flynn, though an officer “with various entities within the Uncommon Schools financial group,” did not sit on boards that made decisions and that “no two parties to any of the transactions had common Board members who could control the Board decision.”

Flynn, she wrote, was offered the CFO position while her consulting company was serving as a financial adviser on the Washington Street building project. The firm stopped working on the project when Flynn began working full time for Uncommon. Flynn resigned from Uncommon last year for “personal reasons,” Martinez wrote.

Shifting the debt to local taxpayers

The subsidies received by the charter school support groups go a long way toward repaying bank loans taken out to buy the federal bonds.

But they fall short of repaying them all.

Federal budget cuts trimmed the aid by a small amount — with the public charter school’s rent typically covering any shortfall.

The Friends of TEAM refinanced about half of its bank loans with state-issued bonds last year.

Berg told the state Economic Development Authority in a letter that the bond sale would lower the interest the Friends were paying on tens of millions of dollars of debt and allow it to avoid an upcoming balloon payment — a large payment of principal due at the end of a loan term.

Documents show that the Friends owed $26 million to M&T Bank and almost $16 million to Prudential. An audit shows the company was making interest-only payments to M&T on an $18 million loan and was scheduled to pay the full amount in 2023.

Berg wrote that TEAM Academy’s lease payments “indirectly fund debt service” on its buildings. And, he said, the refinancing would lower the charter school’s rents.

But documents indicate otherwise.

The payments on the refinanced debt will total $72 million in principal and interest over two decades.

All but $24 million will be covered by federal aid. The Friends may shift much of that burden onto a building on Norfolk Street that the group is scheduled to own debt free in 2027. By then, taxpayers would have spent $30 million on that building.

Under that scenario, TEAM’s rent, which is now $350,000 annually, would be increased to an average of $1.8 million, an analysis of bond documents shows.

By the time the refinanced debt is paid off, taxpayers will have spent about $50 million on the Norfolk building, a school they do not own and that presently is sitting empty.

Charter school operators have been getting millions of dollars in cash to acquire property for school buildings by boosting costs in applications seeking the state’s permission to borrow money.

Each time it happens, it adds debt to charter school building projects that are funded with loans from the purchase of state-issued bonds.

All those costs are being borne by the public.

In some cases, federal taxpayers are helping to pay down the debt through a program that covers the interest on bonds for school construction projects. In others, state and local taxpayers are paying the entire amount with charter school rent.

None of the groups involved would discuss the real estate transactions. The state Economic Development Authority, which issued the bonds, said it doesn’t require appraisals or look at other key details of property transactions because it merely serves as a “conduit.” The bonds are sold to investors who lend money for the projects; no state money is used.

In real estate transactions, it’s not uncommon to borrow against the equity in a property. But in some cases involving New Jersey charter schools, private groups that support the schools paid relatively low prices for property and then flipped it to an affiliate, leaving the public to pay a much higher price in the form of inflated rents. In another case, a support group asked to borrow far more than it paid for land.

Either way, the charter school support groups were able to get additional cash for privately owned properties without saying how the money is being spent. Even if the higher price represents a property’s true market value, some experts say it raises questions about why the savings aren’t passed on to the public.

“The market value is whatever they can sell it for. The problem is they’re not actually selling it on an open market. They’re selling it to a related party.”

“So you found a good deal,” said Grace Regullano, an accountant and financial analyst for the Los Angeles teachers’ union. “Why aren’t you sharing the deal you found with taxpayers? Why are you specifically creating a separate transaction and a separate entity that you can extract more from taxpayers?”

Bruce Baker, a Rutgers professor who specializes in education financing, said charter operators are arbitrarily determining the prices of their properties without testing the real estate market.

“The market value is whatever they can sell it for,” he said. “The problem is they’re not actually selling it on an open market. They’re selling it to a related party.”

“So you found a good deal. Why aren’t you sharing the deal you found with taxpayers? Why are you specifically creating a separate transaction and a separate entity that you can extract more from taxpayers?”

The cases reviewed include:

- The Friends of TEAM Academy, which supports Newark’s TEAM Academy Charter School in real estate deals, arranged for a related company to purchase land on which to build a high school for less than $200,000. Bond documents, however, listed the cost of the land as $1.3 million.

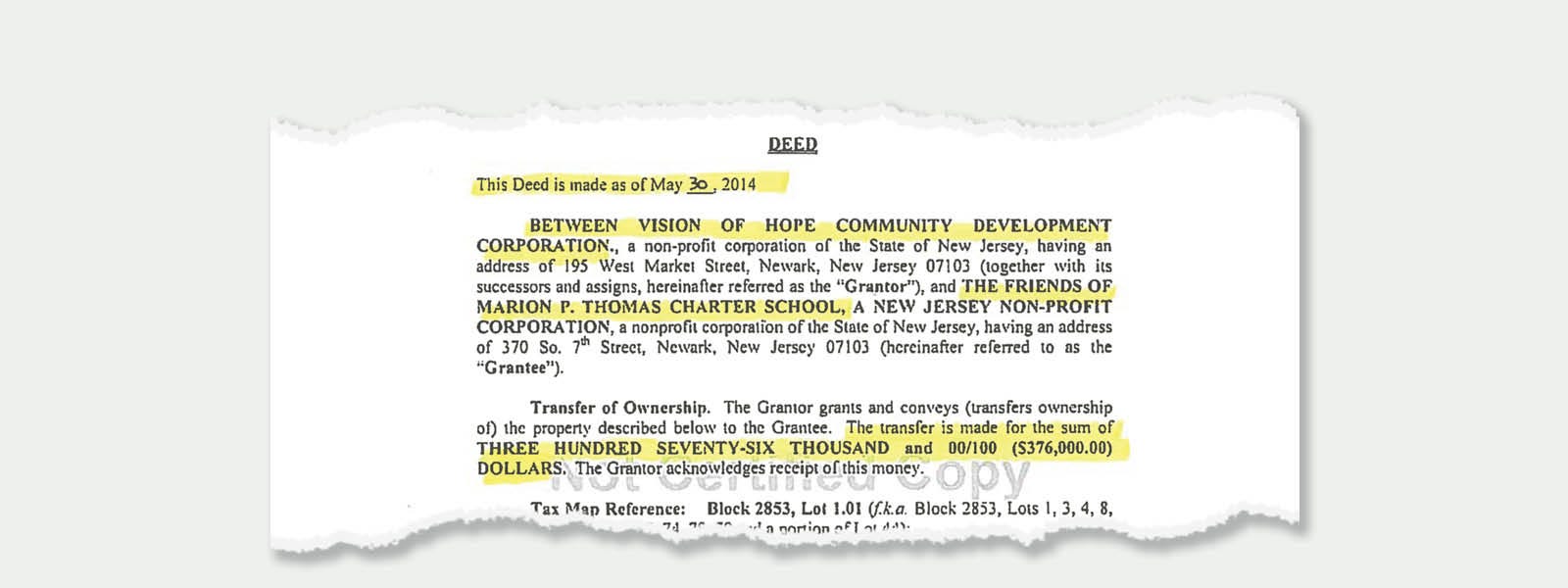

- A group supporting Marion P. Thomas Charter School purchased a vacant lot in Newark for $376,000 in 2013. It turned around the same day and sold it to a subsidiary company for $2.17 million, the price listed in bond documents.

- Companies that owned real estate for TEAM Academy Charter School sold two buildings to a related company for $13.5 million in 2013. The two buildings had been purchased within the previous eight years for a total of $5.7 million. The higher price was listed in documents asking the state to issue bonds to pay for the purchase and renovation of the buildings.

How taxpayers paid an extra $1 million for a Newark charter school

More than eight years ago, a TEAM Academy Charter School official told a government agency about plans to obtain money for the construction of a high school on Norfolk Street in Newark. The Friends of TEAM, he said, was set to pay $192,000 for the land. A company with ties to the Friends group later bought it for that price.

But the price listed in bond documents was much higher: $1.3 million.

Ryan Hill, then TEAM’s CEO and now the head of KIPP New Jersey, the school’s management company, wrote in a 2010 letter to a state agency that approved a bond issue for the project that the difference between the two prices represented the Friends’ “equity contribution to the project.”

A total of $28 million in bonds was issued for the project, based on the higher figure.

That bumped up the cost to taxpayers.

The difference — $1.1 million — is being paid with a combination of federal aid and the public charter school’s rent to use the building, which comes from state and local taxes.

An appraisal conducted by the Leitner Group of New York City determined the market value of the land to be $1.3 million in October 2010.

TEAM Academy provided the appraisal — along with appraisals of other buildings — in response to a public records request. It did not respond to questions.

One property, two sales, a sixfold price hike — on the same day

More than four years ago, the Friends of Marion P. Thomas Charter School purchased vacant land on Sussex Avenue in Newark for $376,000. The group bought it from a church group that had ties to the school.

The Friends then turned around and sold the property to a subsidiary for $2.17 million.

Both sales took place on May 30, 2014, Essex County property records show.

The property is now the site of Marion P. Thomas’s high school, a project funded largely with $35 million in federal bonds issued by the state Economic Development Authority that will provide almost $31 million in federal aid to the Friends over more than two decades.

Bond documents say the higher sales price for the land is "equal to the appraisal value of the Project property.”

The Economic Development Authority said it did not possess a property appraisal for the project, or for other charter school transactions detailed in this story. The authority said it does not require appraisals because it is merely a “conduit issuer” in such deals.

However, public money repays debt — in the form of charter school rent, which comes from local school taxes, and a federal aid program that covers the interest on some school construction bonds.

“Once you say ‘public money,’ I say, ‘Who’s checking and making sure it’s legitimate?’ ” said Donald Campbell, an attorney from Bayonne who specializes in commercial real estate and financing.

He added that banks require appraisals before making loans for property purchases.

The Friends of Marion P. Thomas were scheduled to make a $1.8 million profit on the land sale.

They sold the land to a subsidiary called MPT Facility. Then, according to bond documents, they returned the profit to the subsidiary as part of a $5.5 million loan at 10.6 percent interest.

“Once you say ‘public money,’ I say, ‘Who’s checking and making sure it’s legitimate?’ ”

The loan covered additional expenses and items that were “otherwise ineligible to be financed” by the bonds, according to bond documents. Those costs were not specified in the documents. Officials with the charter school and its private support groups declined to discuss the transactions.

MPT Facility is repaying the loan with its sole source of income: lease payments made by the public charter school. The Friends’ profit from the sale of the land will add $4.3 million to what taxpayers are paying in principal and interest on that loan.

The Marion P. Thomas Charter School was not directly involved in the deal, other than paying rent to cover the building’s debt. In response to a public records request, a school official said he did not have a copy of the appraisal or other documents related to the value of the building. He directed questions to MPT Facility.

The executive director of the Friends group, Garvey Ince, did not respond to messages and declined to comment when reached by phone. MPT Facility’s top board members also declined to comment.

The sale came out of the school’s close relationship with the New Hope Baptist Church and a church-based group called Vision of Hope.

Vision of Hope had been created to develop a community center that would include a school on land that had been purchased from the city, said Ernestine Watson, who served as the group’s president. The organization borrowed money from the church to buy the property. She said that the 2008 recession led to a change of plans and that the larger center was abandoned, leaving only the school to be built.

MPT Facility put another $75,000 into the project, buying a piece of land that was used as a parking lot. Watson said her group didn’t have the money to buy it. MPT Facility then gave the land to Vision of Hope, which combined it with other parcels and sold it to the Friends group for $376,000.

Watson said Vision of Hope used the proceeds to repay the church loan.

She said it was her understanding that the land was being “sold to the charter school,” adding that she did not know about the private companies involved in the transaction or about the subsequent sale to MPT Facility.

“I wasn’t involved with how they did all that,” said Watson, who is now a board member of the Marion P. Thomas Charter School Foundation, which raises money for college scholarships.

Related companies sell to one another, increasing prices and public costs

TEAM Academy had been renting two buildings in Newark for years when they were sold in 2013 for a total of $13.5 million. That was $7.8 million more than two private companies — both of which were created to support the school in real estate deals — had paid for them within the previous eight years.

They sold them to Ashland School Inc., anothe private group formed to support TEAM Academy.

The public charter school continues to lease the buildings.

Its $1.5 million annual rent is almost twice what it was a decade ago. More than half of that amount pays for the transfer of two buildings that the charter school’s support groups already owned.

“The presumption is that the bond counsel has reviewed it and it is eligible."

The state Economic Development Authority issued almost $21 million in bonds in late 2013 to pay for the purchase of the buildings — one on Ashland Street, the other on Custer Avenue — and to cover renovations, including the addition of athletic fields and the construction of a gym.

Timothy Lizura, the authority’s director at the time of the bond issue, said he did not know why the buildings sold for as much as they did in 2013, but he added that improvements made before the sale might have increased their value. The authority’s attorneys had examined all the expenses associated with the project, he said.

“The presumption is that the bond counsel has reviewed it and it is eligible,” Lizura said.

Appraisals prepared for TEAM Academy valued the two buildings at a combined $13.5 million in late 2012 and said that more than $7.5 million in improvements had been made to them over the years.

The reports did not specify when the improvements were made or how they were funded.

It’s not clear how all the money from the sales was used, but documents show some of it was slated to pay down almost $9.2 million of debt related to three other properties.

The Friends of TEAM, a support group at the center of the charter school’s real estate and financial transactions, was prepared to use money from the sales and “other available cash” to pay down principal on a bank loan, according to a 2013 financial statement attached to bond documents.

Another document shows the repayment was to be made “at the time” the bonds funding the purchase of the Custer and Ashland properties “are issued.”

And in a financial document from 2014, the Friends said the Custer Avenue and Ashland Street properties had “book values” that totaled about $11.1 million when they were sold in 2013.

That’s $2.4 million less than the sales price.

Email: koloff@northjersey.com and rimbach@northjersey.com

This story was changed to correct the spelling of Diane Flynn's first name