By 2010, four years after it opened, the Central Jersey Arts Charter School in Plainfield was in trouble.

The state had just put it on probation for a host of deficiencies, ordering it to limit spending, develop a curriculum and address problems with its board and student achievement.

Yet little more than three weeks later, a state agency voted to issue bonds that allowed a fledgling nonprofit called the Friends of Central Jersey Arts Charter School to borrow $8.2 million to buy and renovate a building for the school to rent and, one day, potentially own.

It was a loan whose repayment was based on the tax dollars flowing to the public charter school.

The Friends quickly ran out of cash, and about six months later approached a different state agency seeking millions of dollars in additional financing to finish the project without explaining why they had come up short. The next year, another $1.7 million in bonds were issued, this time with the federal government picking up most of the interest.

While the Friends were permitted to borrow nearly $10 million, the school itself was floundering. A financial report covering the 2010-11 school year stated that Central Jersey Arts was “not in good financial condition” and raised “substantial doubt” about its survival.

The building opened with fanfare as contractors went unpaid. The next year, the school was back on probation, where it stayed until the state shut it down in 2015 for weak finances and “dismal” academic performance — but not before dumping more taxpayer cash into a now-defunct for-profit management company in the hope of turning it around.

This is the story of a charter school that failed, and a building that used up millions in public dollars and continued to receive federal aid long after it was left vacant. It’s a story about dubious decisions by multiple state agencies, one that raises questions about the use of public money and the oversight of private groups that own real estate for public charter schools.

“It didn’t feel right, and I remember saying I would never do it again. And it soured my whole taste for charter schools completely.”

A review of thousands of pages of documents and dozens of interviews reveal a problem-plagued building project that suffered delays, was fined by the state and became tangled in legal action and liens. They show a school whose finances were in such bad shape that auditors said it would be tough to identify fraud or theft, and a program that churned through teachers and business administrators at an alarming rate.

The staff moved to unionize. The school board quit en masse. At one point, a janitor was doing the books.

Ultimately, the education of hundreds of students was disrupted. The public lost its investment in the school and the building. And although another charter school is now leasing part of the space, the rent payments aren’t high enough to cover the debt on the property, leaving bondholders with the possibility of significant losses.

Today, real estate entrepreneurs from Newark sit on the Friends group’s board, and the building has been considered for use as a storage facility and an assisted-living center. It was listed for sale at $7.95 million at one point.

What remains of a once-promising charter school and an ambitious building project is finger-pointing, contradictions and suspicions.

A former president of the Friends board said that something about the project "didn't feel right."

“I remember saying I would never do it again,” said Abdul Majid. “And it soured my whole taste for charter schools completely.”

One of the school’s last board presidents, who resigned a little more than a year before it closed, described her experience as “a nightmare.”

“You know, the bottom line is greed should not supersede education,” said Dawn Armstrong, referring to the school's management company. “Honestly, I felt within a very short period of time that everyone that came through the doors saw us as this bleeding school and they figured out how can we step in, make some quick money. What difference does it make, because they’re hemorrhaging anyway.”

Problems surfaced early

Central Jersey Arts Charter School opened in the fall of 2006 with 223 students in kindergarten through fifth grade. It became known simply as CJACS – pronounced SEE-jax.

An early web page said its mission was to instill in its young charges “a desire to learn and grow academically and socially.” The arts, it said, “will be used as a vehicle to inspire children.”

Its lead founder, Shamida Coney, owned and operated a dance studio in Plainfield. Her mother, Cora Coney, then a social worker in the Newark school district and part-time realtor, was also among its founders. Three parents — a public school librarian, a human resources manager and an artist and business owner — completed the founding group.

“I put my heart and soul into that school. It was a fight the whole way. I don’t understand why people did what they did. It really is very difficult to talk about. I’m going to leave it at that.”

One teacher called the school “a diamond in the rough.” Another said that “everybody wanted to make it work.”

Early on, the state investigated multiple allegations about the school. Many were unsubstantiated or were rectified by the time the probe was completed. The school had, for example, taken steps to address disciplinary problems and a rodent and insect infestation in its first building, which it rented.

It did, however, chastise the board — then headed by Cora Coney — for hiring Shamida Coney as the school’s “arts-in-education coordinator.” The job, which paid up to $70,000, entailed supervising staff, developing and directing an arts-integrated curriculum, and managing school-wide programs and events. She had also received fees associated with the start-up of the charter at a rate of $4,750 a month.

Investigators with the state Education Department’s Office of Fiscal Accountability and Compliance said in a 2007 report that Shamida Coney “does not have a degree and holds no certification in New Jersey.” They wrote that she was “not properly qualified” to “perform certain functions she was hired to provide.”

The state recommended that $56,000 of $70,250 in billings be refunded because it had been paid with state aid; the rest was charged to a start-up grant program. Investigators said Shamida Coney had the highest salary in the school and that “the circumstances surrounding her appointment invites suspicion.”

“Awarding this position to the founder and daughter of the charter school board president and paying her in this manner gives the appearance of favoritism,” they wrote.

Shamida Coney went on to serve as the school’s “lead person.” She acknowledged that CJACS was “not pristine or the perfect organization.” She declined to comment on its financial or academic issues, saying that there “were a lot of reasons why it didn’t do well” and that it was not something “I care to revisit.”

“In general, I think there was a lot of political motivation against the school,” she said.

Cora Coney, too, would say little.

“I put my heart and soul into that school. It was a fight the whole way,” she said. “I don’t understand why people did what they did. It really is very difficult to talk about. I’m going to leave it at that.”

Some said guidance from the state was lacking and the board was ill-prepared. Kathleen Moore, a former board member who did a turn as president, said the state-required training “was no help.”

“When you get on the board of a charter school you need to know a lot, and I just really felt like I was drowning most of the time,” she said. “When I look back now I just think, you know, it was really a wonderful idea. When you’re in the middle of it, you just can’t see a way out.”

Borrowing begins for multimillion-dollar school

The push for a new building began in earnest in 2009.

The rented building, Shamida Coney said, “was suitable for the initial opening, but we needed something more conducive to learning.”

The school began working with an architect. Erick Torain, the financial adviser to the as-yet-unformed Friends, contacted the state about financing. Documents show he was paid at least $314,000 for a host of services, from real estate negotiation to project development and management.

That November the Friends of Central Jersey Arts Charter School was created as a nonprofit corporation and was soon granted tax-exempt status by the IRS. The charter school, meanwhile, agreed to reimburse the Friends up to $50,000 for out-of-pocket expenses, records show.

The Friends group was a separate organization with its own board that would have no assets other than the school building and its lease with CJACS.

The arrangement allowed the charter school’s operators to borrow money and pull funds from the school to pay it back — without running afoul of state regulations. It kept the property in private hands, placating lenders who often prefer it that way.

“It was not a good building to start with; it had a lot of problems.”

It also meant the project did not have to comply with public bidding laws — and Torain said it didn’t.

Early in 2010, the Friends applied to the New Jersey Redevelopment Authority for $8.2 million in bond financing. By then, they were under contract to buy a building on South Avenue in Plainfield for $3.8 million.

Majid, then the Friends’ president, said it was not his first pick, but it had office space, an elevator and better access than another contender. Still, he said, “it was not a good building to start with; it had a lot of problems.”

The property included a 38,000-square-foot building that the project architect, Ray O’Brien, said had at least four additions. There was also a smaller structure that the school hoped to one day use for a theater program; it, too, needed work. And there was a parking lot separated from the school by another property.

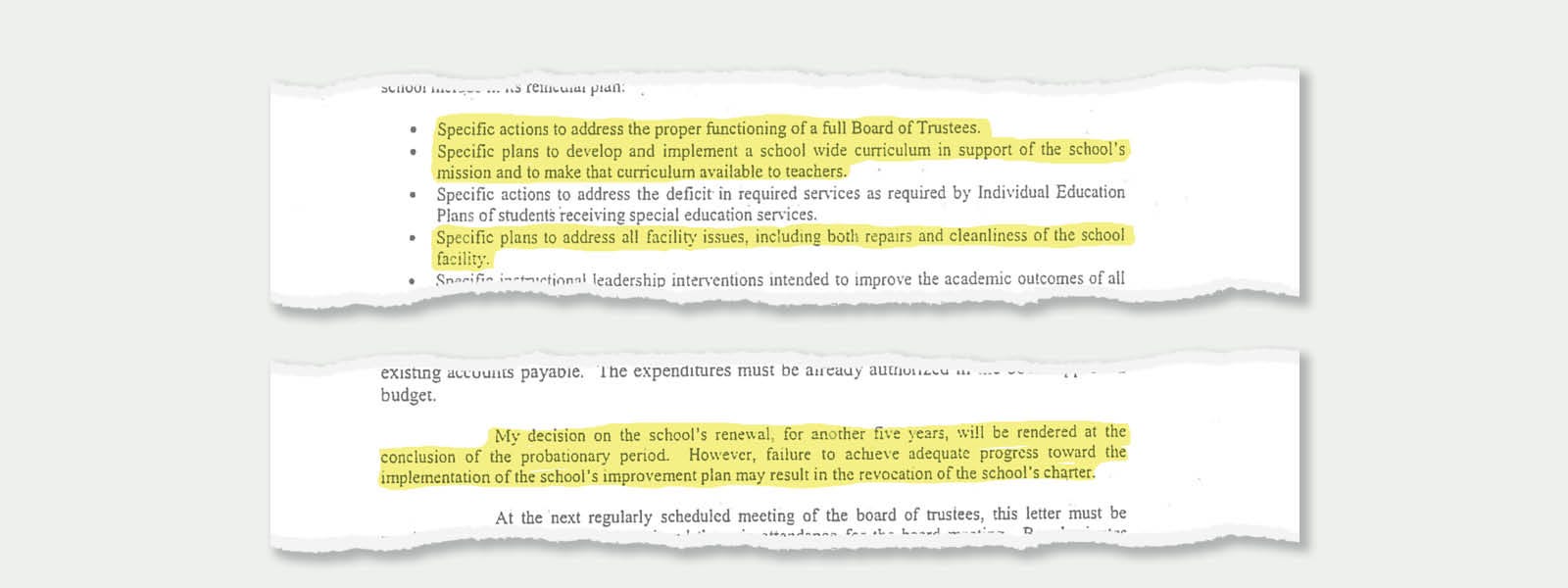

On March 1, as the financing moved forward, the school received bad news: It was being placed on a 90-day probation. In a letter, the state’s acting education commissioner at the time, Bret Schundler, demanded a remedial plan, listing seven areas that he said it was “imperative” for the school to address, including: student achievement, "the proper functioning of a full Board of Trustees” and a “deficit” in special education services.

Schundler also ordered the school “to develop and implement a school wide curriculum” in support of its mission, and instructed it to limit spending to necessary, budgeted expenses, such as salaries, benefits and rent. He also asked the school to address issues with its building, including "repairs and cleanliness."

Still, on March 25, the redevelopment authority passed a resolution approving the bond sale.

A month later, Schundler sent the school another letter, this time renewing its charter for five years, lauding its progress and allowing it to boost enrollment to 395. There was no mention of the 90-day probation.

The bond financing closed soon after, the Friends bought the property, and the charter school signed a lease with a $744,000 annual base rent — then more than 16 percent of the school’s total revenues.

The agreement called for annual rent increases and passed all costs — including taxes, maintenance and insurance — to the charter school. The school also agreed not to borrow money outside of ordinary expenses without the permission of the Friends or its lender, a provision that was later changed to require the approval of both. The school could buy the property for the outstanding debt.

Leslie Anderson, the executive director of the redevelopment authority, declined to comment on the bond sale.

An official with Hamlin Capital Management, which placed the bonds with investors, cited Schundler’s letter when asked why it moved forward with the deal. Jeremi Roux, Hamlin’s general counsel and chief compliance officer, said in an email that an audit from the previous fiscal year was sound and showed no “material weaknesses.”

Roux said charter school investments carry “significant risks.” He noted that investors were required to be “Accredited Investors and Qualified Institutional Buyers” — essentially wealthier, sophisticated investors and institutions for whom the bonds would be a small part of a larger portfolio.

Given the limited exposure, it’s unclear why Parker Stitzer, a Hamlin partner, visited the school on more than one occasion as its troubles mounted.

Roux did not say. He declined to answer most questions.

Richard O’Neill, whose firm, Renaissance School Services, was hired to manage CJACS in its final years, said Stitzer monitored the school’s progress in person “because he was trying to protect his investment.”

O’Neill said Stitzer was usually with Torain, the Friends’ financial adviser, who records show teamed with Hamlin on a deal involving another charter school in Newark.

It, too, has closed. Investors in that project suffered losses. And investigators in the state Education Department recommended that the state Attorney General’s Office "determine whether there was any criminal involvement regarding issuance of the lease and bonds."

The Attorney General’s Office declined to comment.

More money, little explanation

It wasn’t long before the Friends of Central Jersey Arts Charter School looked to another agency — the state Economic Development Authority — for more money.

In January 2011, Torain submitted an application to the agency on behalf of the Friends for another $3.55 million in financing.

An EDA memo indicates the authority found the request to be excessive.

“Per sources and uses there is only $1,050,000 needed for new money,” an official wrote, noting that “the rest was provided” in the earlier bond sale.

The EDA issued $1.7 million in bonds. The interest on $1.4 million of that — about $80,000 a year — would be picked up by the federal government under a school construction program.

Hamlin again placed the bonds with investors. And CJACS signed a new lease with the Friends that boosted its annual base rent to $773,000. It would be more than $815,000 by the time the school closed, all of it paid by taxpayers.

The group did not explain in its application to the EDA why the first round of funding was insufficient to pay for the project. The Friends told the EDA in a November 2010 letter that they “always contemplated another round of funding,” but there was no suggestion of that in the paperwork for the first bond issue.

Torain said the reason was asbestos; there was much more of it in the building than expected. Removing it, he said, cost “north of $1 million.”

It’s a figure some contractors dispute, and state officials say the work was mishandled from the start.

As the project got under way, the Department of Community Affairs received an anonymous complaint about illegal asbestos abatement at the site. The DCA said it issued a stop-work order because “the job was being done by an unlicensed contractor and without the services of an Asbestos Control Monitoring (ASCM) firm.”

An ASCM is required for work on schools and public buildings. Building owners — or their agents — must also notify the DCA 10 days before the start of such a job. That did not happen.

The DCA said Torain Construction — which is owned by Erick Torain, the Friends' financial adviser — was overseeing the project when “work was performed in the school by unlicensed contractors who disturbed asbestos containing material.”

The Friends were fined — and paid — $5,000. The project was at a standstill for a month.

Dejan Antic, whose company Global Safety Contracting removed asbestos from the building, said there was much more asbestos than the survey indicated, the job took longer and the price mushroomed.

But he doubts the cost exceeded $1 million, recalling that his piece was at most $360,000. An environmental monitor for the site said he could not remember specifics of the job but “would be shocked” if it was that high.

Removing asbestos for a school is a costlier endeavor, one with stricter rules and more monitoring than in other types of buildings. Antic said the overriding issue was that he wasn’t told — and the survey he was given did not indicate — that the building would be used as a school.

Contractors complain, lawsuits follow

The asbestos problem was just one in a string of issues. The Friends were sued by their first architect. The group sued the city of Plainfield over a drawn-out approval process. The school’s former landlord took it to court for back rent and damages to his building.

And later, as it faced a cash crunch, the school would learn it was on the hook for more than $80,000 in property taxes that Plainfield officials said predated the building’s use as a school.

Contractors say they scrambled to get the building completed on time.

In April 2011, the school moved in; there was a ribbon-cutting in May. The next month, contractors began filing liens against the property for unpaid work. Lawsuits would follow.

“It took me three or four years to pay it back. When somebody screws you out of that kind of money, it hurts, especially when you’re not a real big company.”

The Friends countered in court papers with accusations of poor-quality work, including a leaky roof, mold and other water-related damage, plumbing issues and poor drainage. There was flooding in the school, the Friends said, on the eve of its grand opening.

The group, which filed a claim on the performance bond, eventually asked a judge to consolidate disputes related to the project and raised objections to the general contractor's move to take the matter to arbitration.

John Tomic of E-Tomic General Contracting maintains that, once the Friends had a certificate of occupancy, in the group’s eyes “we became the worst contractors.”

“Everything that was wrong with the building was things that we suggested to him to do outside of the contract, which he definitely wouldn’t listen to,” Tomic said, referring to Torain.

And Tomic said flooding was caused by a storm drain issue that could have been resolved in a weekend for $38,000.

A court file on the matter grew as lawyers for subcontractors weighed in.

Anthony Marino, whose company, Marino Paving, is owed $58,000, said he took out a loan to cover the bills for materials he bought for the job.

“It took me three or four years to pay it back,” he said. “When somebody screws you out of that kind of money, it hurts, especially when you’re not a real big company.”

Shah Faisal of New Jersey Mechanical Contractors said his company is out $91,000.

“By the time we finished the project they said, ‘We have no money left,’ ” he said.

A state Superior Court judge ordered the matter to arbitration in the fall of 2012.

“That was one of my reasons for leaving because it felt weird. I don’t want to disparage anybody’s character, but something about it didn’t seem on the up-and-up. It just didn’t seem right.”

The Friends’ lawyer went back to court, this time asking to be removed from the case involving the contractors because his firm had not been paid.

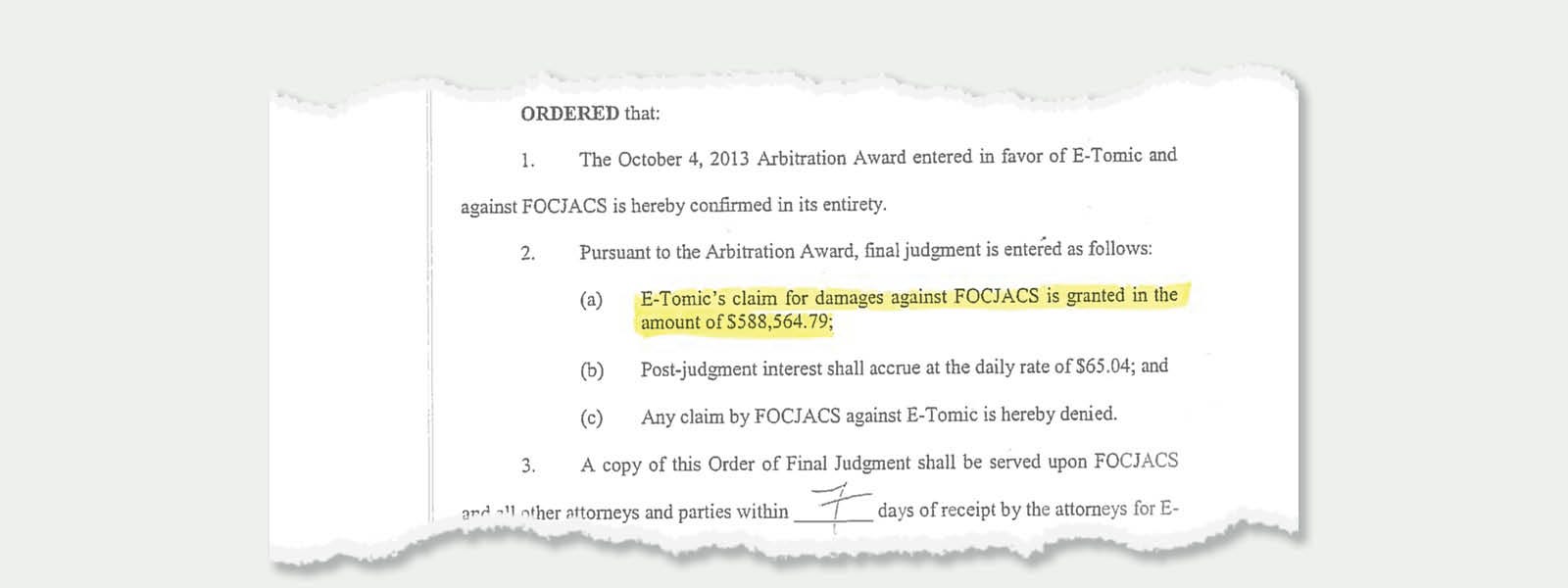

In the fall of 2013, an arbitrator awarded $588,564 plus $65 a day in interest to the general contractor, E-Tomic. A good chunk of that was owed to subcontractors.

A judgment was entered against the Friends, who did not show up for the arbitration, according to documents.

It’s never been paid.

“Let me tell you, there’s a lot of money sitting somewhere that somebody got that we don’t know about,” Tomic said.

Torain has a different take. He denies refusing to do necessary work.

“To my knowledge the contractors were paid,” he said.

He waved off any suggestion that funds were misused because their release was up to the bond trustee and project monitor.

“At no point would anybody at Friends be a recipient of that cash,” he said. “Neither I nor the school could have access to the funds.”

The project monitor, Rob Hartmann of Hartman Consulting in Spivey, Kansas, did not return calls.

The bond trustee, Wells Fargo Bank, declined to answer questions.

Majid, who left the Friends after the school building was completed, said he remembers feeling “uneasy” and talking to people “about who got paid what and what got paid to who. I was like, that’s a lot of money.”

“That was one of my reasons for leaving, because it felt weird,” he added. “I don’t want to disparage anybody’s character, but something about it didn’t seem on the up-and-up. It just didn’t seem right.”

Cash flow issues

As the Friends increased their debt based on the charter school’s ability to repay it, documents show that the school’s finances were in turmoil.

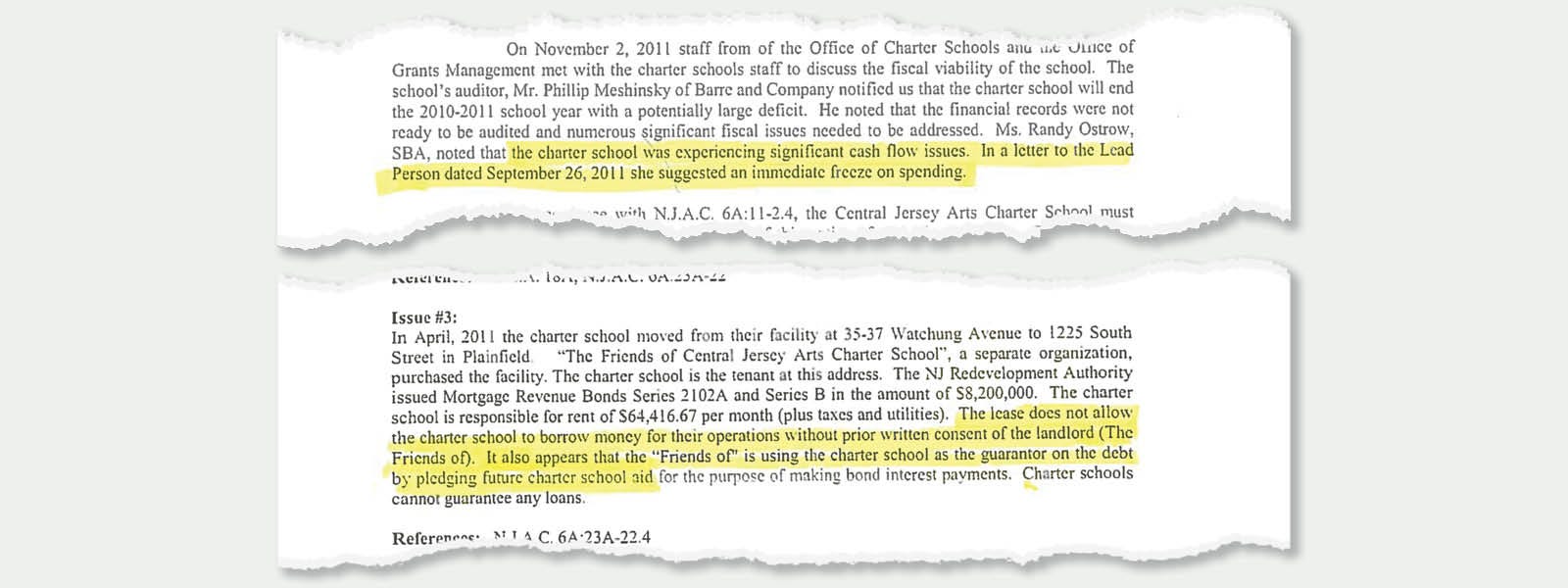

It had “significant cash flow issues.” The school’s business administrator suggested “an immediate freeze on spending” in September 2011.

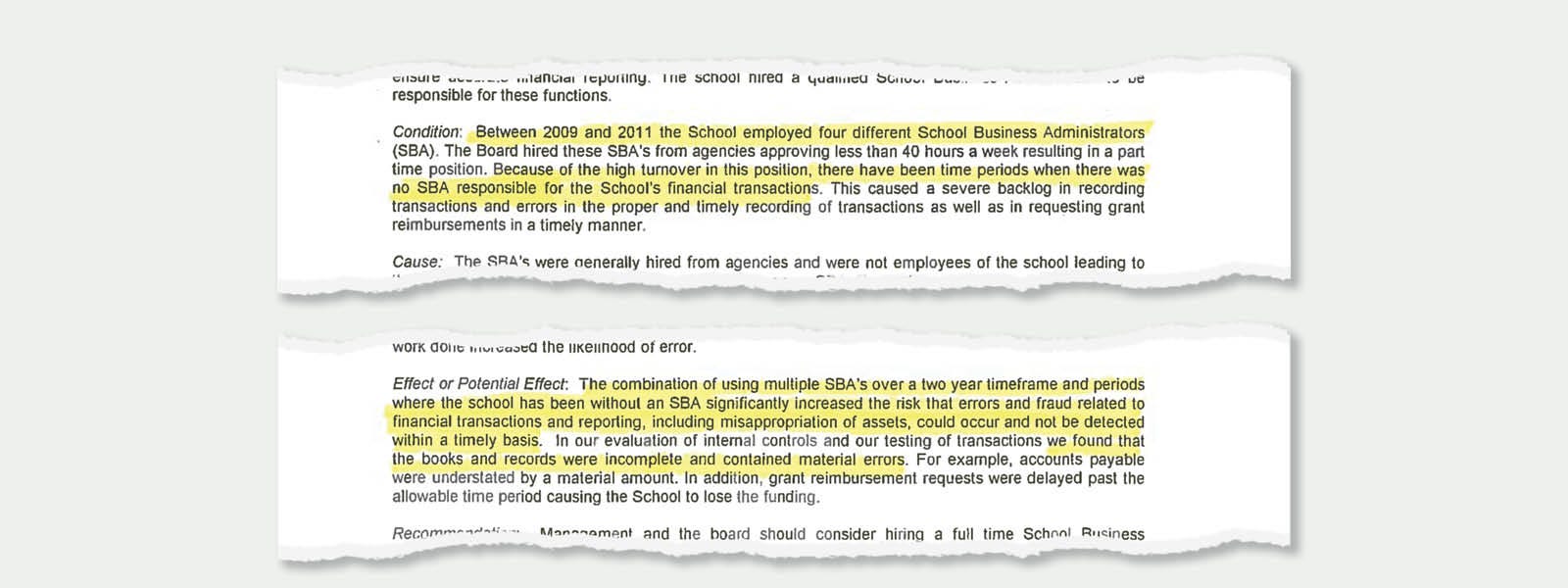

A financial report covering the 2010-11 school year was grim. Books and records were incomplete and contained errors. The board had been in the dark about school finances for long periods. And there was “a severe backlog” in the “proper and timely recording of transactions.”

The spending of federal money designated for low-income children was not properly documented. And the school had lost money because it failed to request grant reimbursements on time.

Auditors wrote that the school “is not in good financial condition presently” and raised “substantial doubt about its ability to continue as a going concern.”

The report also noted an “unusually high turnover” in business administrators. From 2009 to 2011, the school had four of them, all of whom worked part time and were not school employees. They were employed by agencies and none were approved to work a 40-hour week.

There were periods when there was no business administrator “responsible for the School’s financial transactions,” the report said.

During one eight-month stretch, the board made “critical financial decisions without sufficient financial information.” It lacked monthly financial reports and bank reconciliations, for example.

The school’s impending move to a larger facility — including the required approval of additional expenditures like double rent payments — made it a “critical time for the board to have solid financial data,” the auditors noted.

The report put the cost of the move — including the loss of the security deposit from the old location — at $650,000. The school’s landlord, it said, was also seeking money for damage to his property but had yet to file suit.

New problems surface

Central Jersey Arts’ first full year in the new building would be a rocky one.

In January 2012, education officials put the school on another 90-day probation for not operating according to its charter, state statutes and regulations.

The education commissioner at the time, Christopher D. Cerf, ordered another remedial plan, listing in a letter multiple areas to address, most focusing on finances, board oversight and concerns about the new facility.

The school was withholding money from paychecks for benefits but hadn’t sent any of it — $262,976 — to the state health program for a year, incurring penalties. And it was months late in reimbursing the Plainfield school district more than $50,000 due to enrollment losses.

And now, long after the financing had closed and the lease for the new building was signed, state education officials were weighing in. The lease didn’t allow the school to borrow money without the consent of its landlord, the Friends group, the letter noted. And it required the school to pay taxes: “Public schools are exempt from property taxes. Please clarify.”

There was concern, too, that the Friends were “pledging future charter school aid” toward bond payments. Since charter schools can’t guarantee loans, the state asked for clarity on the school’s obligations. The school told the state it had no agreement with bondholders. However, its rent payments were the Friends’ only source of money to repay debt.

Cerf’s letter also asked the school for a copy of the prospectus for the $8.2 million bond issue. But there was no mention of the second round of borrowing. The rent amount cited in the letter shows that state education officials were unaware it had increased.

In May, the school’s probation was extended. New issues had emerged: The school was behind two years on employee pension payments that totaled $116,733 and were accruing interest. And it owed the state $477,468 for unemployment benefits, including $48,000 in interest.

The problems extended to the classroom. Only about a third of pupils were proficient in math and language arts. That put CJACS in the bottom 3.5 percent of all schools in the state. In Plainfield, 10 of 12 district schools that served the same population outperformed it.

In October 2012, the school’s probation was extended yet again.

There was no evidence it had a fully functioning, certified school business administrator. It did not have a full school board. And the board had violated the state’s Open Public Meetings Act by convening in a remote location without adequate public notice.

The school also didn’t have a nepotism policy. The state ordered it to approve one that prohibited “any relative of a board member, lead person, or chief school administrator from being employed” by the school.

Cora Coney, who had been president of the board and still served as a trustee, resigned her post that December. Her daughter Shamida stepped down as the school’s “lead person” the same month.

By then, a for-profit management company was running the school.

'Please help!'

Central Jersey Arts Charter School signed a contract with Renaissance School Services to turn it around.

The company’s fee was 9 percent of all public and private revenues; for CJACS that would mean more than $500,000 annually. Senior managers would be employed by Renaissance. The school would pay the company 130 percent of those managers’ salaries to cover their pay and benefits. Termination of the agreement for anything “but cause” would ring up $500,000 in “winding down costs.”

Some former school officials said the state required CJACS to bring on a management company and that the state favored Renaissance. The Education Department said “there’s no regulatory or statutory mechanism” that would allow it to require a charter school to hire a management company.

Years earlier, Richard O’Neill of Renaissance had been an executive at Edison Schools, a large for-profit manager of public schools, when Cerf was its CEO. O’Neill said Cerf had “zero impact or influence” on the CJACS board’s decision to hire Renaissance.

Within a few months, in addition to academic and financial issues, O’Neill learned about the Friends and their battle with contractors. The Friends’ lawyer asked him if the school would pick up legal costs, and “we refused to pay even a penny,” O’Neill said.

“From my standpoint, the Friends was its own entity, had its own board, cut its own deal — all we were [doing] was paying rent,” he said. The state, he said, viewed that rent as high, and he hoped that one day the bonds could be refinanced to bring it down.

O’Neill said as far as he knew the Friends didn’t hold meetings. He said the school wired money to the bond trustee. And if there was a building issue, O’Neill said, he called Torain, who took it to Stitzer, the partner at Hamlin.

By multiple accounts, Renaissance’s tenure at the school was tumultuous. O'Neill and the board clashed. There was high staff turnover and a vote to unionize. An audit shows a precipitous dip in the amount of cash going toward instruction — from more than half of the school's annual expenses in the 2012-13 school year to about a third a year later.

A former business administrator said: “It was obvious the school was not going to survive.”

A series of emails show that the dysfunction hit a peak near the end of the 2013-14 school year.

In June, the school inducted three new board members. An email to the state from its business administrator, Jill Carson, said the new board appeared ready to end the contract with Renaissance but “needed to know their action would not reflect negatively on the school.”

She wrote that O’Neill was “exerting pressure” about renewing with Renaissance and that the board was “eager to seek advice from counsel to prepare for the fallout which will inevitably occur.”

That same week, O’Neill met with state education officials. A day later, he sent an email to the head of the charter schools office attaching a lengthy list of board actions he termed inappropriate, illegal, or violations of his soon-to-expire contract. His claims ranged from the board not voting in public for over a year to meddling in personnel matters.

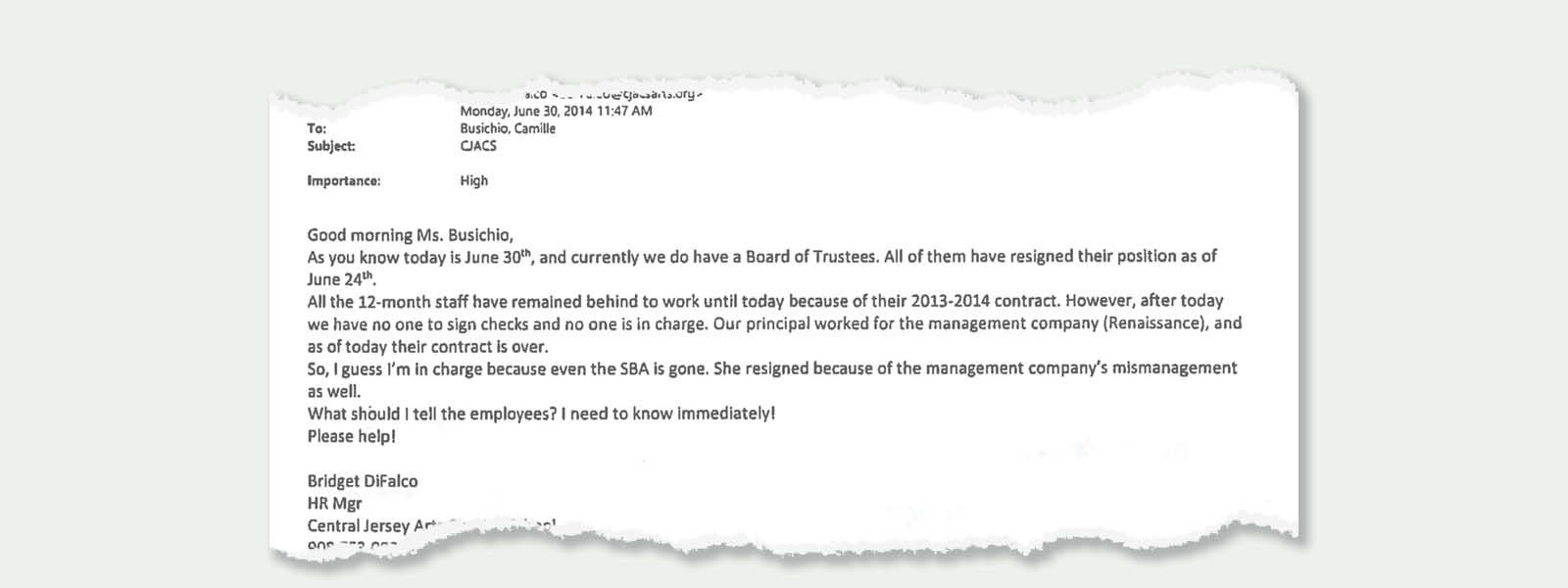

About two weeks later, the school’s human resources manager, Bridget DiFalco, fired off a panicky email to the state.

“As you know today is June 30th, and currently we do not have a Board of Trustees. All of them have resigned their position as of June 24th,” she wrote.

“After today we have no one to sign checks and no one is in charge. Our principal worked for the management company (Renaissance), and as of today their contract is over.”

“So, I guess I’m in charge,” she continued, noting that the school’s business administrator had resigned “because of the management company’s mismanagement.”

“What should I tell employees? I need to know immediately! Please help!”

'Many more unanswered questions'

CJACS continued for another year, with Renaissance as its manager. O’Neill reassembled the board.

In his updated contract, O’Neil forgave two months of fees. But a new provision entitled Renaissance to a $150,000 payout even if the pact expired naturally.

At the end of October 2014, state officials made a pivotal visit to the school.

A report shows they questioned whether school administrators and Renaissance had the capacity to improve student achievement quickly. The staff complained about a lack of transparency and support from Renaissance.

“There is a lack of evidence the school is providing its students with a quality education.”

Officials wrote that there was “no evidence of a strong, cohesive and school-wide curriculum” or the ability to develop and implement one. All the board members were new, and it was unclear if they could provide the oversight and leadership needed to turn the school around swiftly. They didn’t seem to have a plan.

Days later, the school’s probation was extended into the new year. Education officials visited again in December and returned near the start of 2015.

By March it was over. David Hespe, who had taken over as education commissioner, refused to renew the school’s charter and ordered it in a letter to cease operations at the end of the school year.

“There is a lack of evidence the school is providing its students with a quality education,” he wrote.

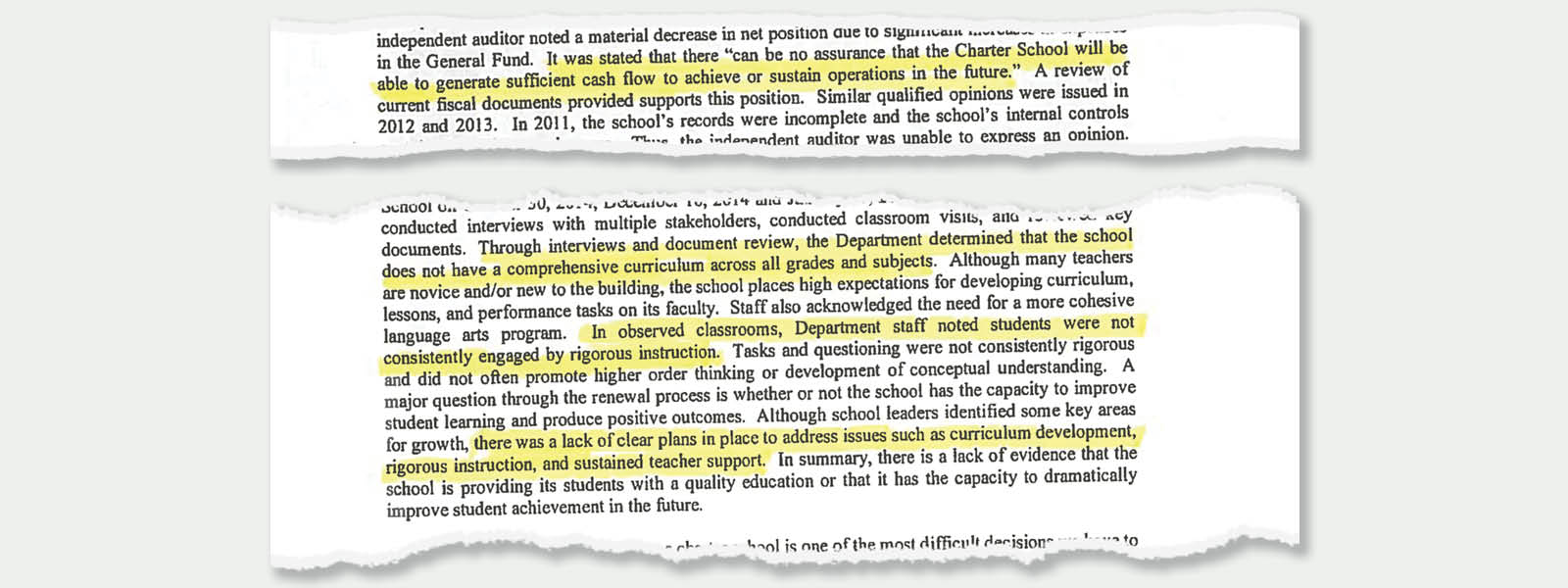

Academic results, in his view, “remained dismal.” The school lacked “a comprehensive curriculum across all grade levels.” Students were not “consistently engaged by rigorous instruction.” The financial picture was bleak. An auditor said there “can be no assurance that the Charter School will be able to generate sufficient cash flow to achieve or sustain operations in the future.”

Charmaine Walker taught at the school for one year, its last. Teachers did their best, she said, but there didn’t seem to be any follow-through by the administration. She said the language arts curriculum was lacking for the grades she was teaching, and there weren’t enough books and supplies or a consistent discipline policy.

“The vision was there,” she said, but she added that there was a lack of leadership and support.

“The school could have been a really great school if things were in place, if money was spent appropriately,” Walker said. “Especially on curriculum and after-school activities and supplies.”

“The school could have been a really great school if things were in place, if money was spent appropriately, especially on curriculum and after-school activities and supplies.”

O’Neill, who closed his company in 2017, said he thinks the state gave up too soon. He said grades were starting to turn around — records show math scores had recently jumped. And he said the financial situation was “not rectified, but it was vastly improved.”

“Frankly,” he said, “I think the state was just sick of dealing with the problems at the school.”

The school’s contents were auctioned off for $59,227.

But its books continued to raise questions. The CJACS trustee, Phil Meshinsky, told the state via email that the school’s interim business administrator “did virtually nothing from February 2015 to May 2015 when he walked out.”

He said there were numerous mistakes in pension and retirement plans. An earlier audit had errors. And he was concerned by a cash increase that allowed CJACS to show a positive balance the previous year since he couldn’t duplicate the numbers.

“There are many more unanswered questions,” he wrote in an email in January 2017.

In a final report, auditors declined to give an opinion on the school’s finances, citing “a lack of available records.”

Tax money continues to flow to empty building

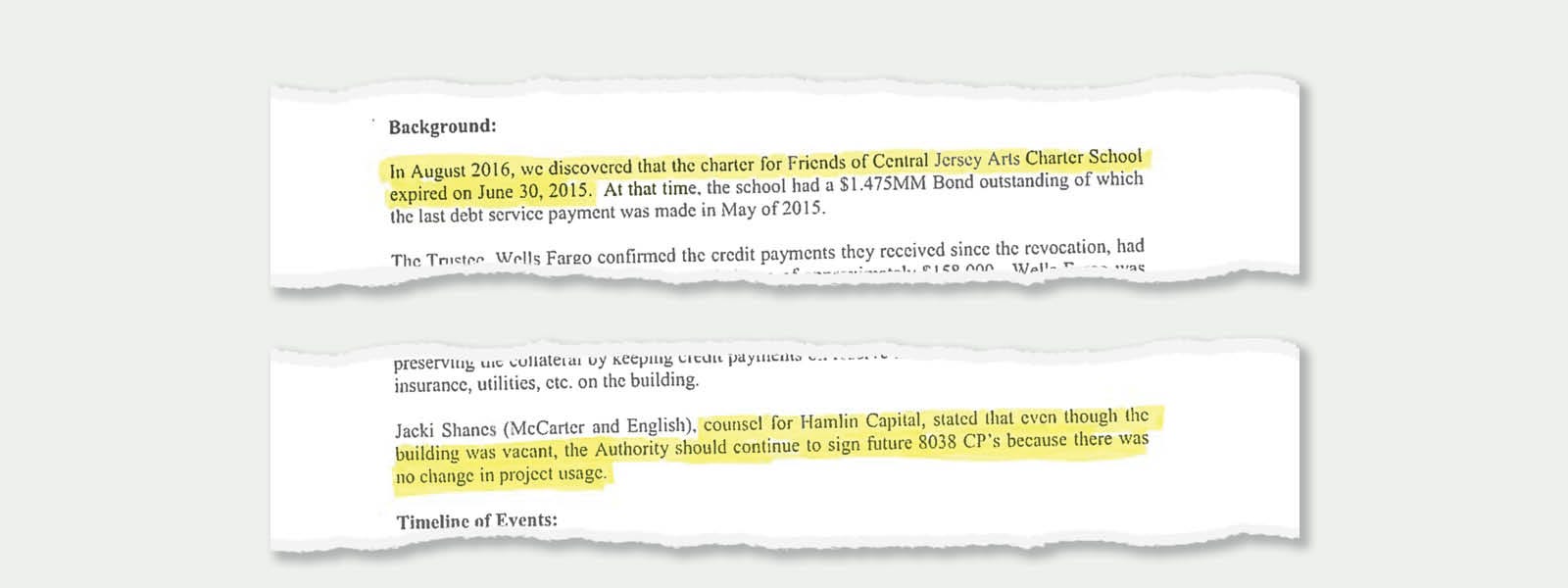

When the school closed, the payments on the bonds that financed the CJACS building dried up. The building stood vacant for two years.

No move was made to foreclose on the property as Hamlin looked for other uses for the building. It directed the bond trustee, Wells Fargo, not to take any action against the Friends.

All the while, federal aid attached to the second round of borrowing — interest payments of about $80,000 annually — kept landing in a reserve account.

Taxpayers were refunding interest on a debt that was not being paid — and for a building that was not being used as a school.

“I was looking at that as well. It wasn’t clear to me exactly how that worked,” said Tim Lizura, who served until recently as the director of the state Economic Development Authority, which issued the federally subsidized bonds. “I take great comfort in that a lot of attorneys were looking at that — including the Attorney General’s Office.”

It is clear from heavily redacted emails and memos that the authority wasn’t aware that the Education Department had not renewed the school’s charter; it “discovered” the closure at least a year later. The emails also show confusion about the federal interest payments, concerns about the state continuing to sign for them, and disagreements about releasing that cash to investors.

Hamlin wanted the interest payments to keep coming; the firm’s attorney told the state that even though the building was vacant, there “was no change in project usage.” It didn’t want the interest to be sent to investors, preferring to keep it on hand for building upkeep. The emails show that the state pressed the firm to release the cash. The Attorney General’s Office was called on to discuss “the risk” of the state continuing to authorize the payments from the federal government.

In 2017, the state signed off on the payments. The bond trustee began making partial distributions of interest that May.

$5 million and counting

Today the Friends still own the building.

The group lost its tax-exempt status in 2013 for not filing multiple returns.

The state twice revoked its business certification for not filing annual reports.

Two scant tax filings were sent to the IRS in 2014. The only name on them is Erick Torain’s.

“The Friends group was completely gone, so I stepped into the breach,” he said.

Real estate entrepreneurs now fill the void.

In August 2017, the state reinstated the Friends with a new slate of officers.

The group’s president, David B. Berkowitz, and its treasurer, Alan Wellman, are co-founders of Assurance Realty Group in Newark, which, according to its website, is “an entrepreneurial driven, privately owned commercial real estate brokerage and advisory firm.” It lists charter school “acquisition, disposition, and development” among its services.

Berkowitz declined to speak with reporters; his office referred questions to Hamlin. He and his companies have worked on projects involving Friends groups for two of the state’s largest charter schools: TEAM Academy and Marion P. Thomas, both in Newark.

Hamlin would not discuss Berkowitz’s role on the Friends group; Hamlin's attorney said “we refer you right back to them.”

College Achieve Central Charter School now uses part of the Central Jersey Arts building. In the 2017-18 school year it paid more than $460,000 in rent and start-up fees to its management company, which has a lease with the Friends group. The charter school will pay close to $400,000 this school year.

It’s unclear if College Achieve plans to stay in the building long-term. The only lease provided by the school expires in June 2021.

Wells Fargo notified investors of the new tenant but cautioned that “it’s premature to predict what recovery, if any, bondholders will ultimately receive on their investment.”

The building was awash in tax liens until the end of last year, when more than $550,000 was paid to the city of Plainfield in three separate checks: one from the Friends, one from Berkowitz, and another from his company Assurance Realty.

More than $5 million in public money — including rents and federal subsidies — has been spent on the building.

Timeline – Central Jersey Arts Charter School

The Central Jersey Arts Charter School opened in 2006 in a rented building in Plainfield, with a goal of blending the arts and academics. The growing school ultimately wanted a new site — one that a founder said “would be more conducive to learning.” As it approached its first charter renewal, it embarked on a building plan. What follows are some of the ups and downs of the school and its building project:

Nov. 4, 2009

The Friends of Central Jersey Arts Charter School incorporates in New Jersey as a nonprofit; an IRS tax-exempt designation follows.

Feb. 17, 2010

The Friends apply for bond financing to the New Jersey Redevelopment Agency (NJRA).

March 1, 2010

The state Education Department puts the school on probation for 90 days and orders it to limit spending, citing concerns about its board, curriculum and student achievement. It also asks for a plan to address facility issues, including repairs and cleanliness.

March 25, 2010

The Friends are approved for $8.2 million in bond financing. The same day, the initial architect on the project files a claim against the property for $122,055 based on the Friends’ impending ownership.

April 30, 2010

The state education commissioner informs the school its charter is being renewed for five years, lauding its progress and allowing it to boost enrollment to 395. There is no mention of the 90-day probation. He says its improvement plans will be monitored.

May 20, 2010

NJRA bond financing closes. The Friends purchase the property on South Avenue in Plainfield for $3.8 million. The school signs its first lease with the Friends; it has a $744,000 base annual rent.

July 27, 2010

The state issues a stop-work order at the site due to asbestos removal issues, including use of unlicensed contractors.

Aug. 25, 2010

Work resumes at the site.

Nov. 2010

Letter indicates the Friends look to the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (EDA) for additional financing.

Jan. 4, 2011

Erick Torain, the Friends’ financial adviser, applies to the EDA for $3.55 million in new funding for the project. An EDA memo indicates the authority finds the request excessive.

Jan. 5, 2011

The state issues a violation notice and an order to pay a $5,000 penalty to the Friends of Central Jersey Arts Charter School in relation to the asbestos removal.

Feb. 28, 2011

The school’s lease is amended, raising its rent to $773,000 annually.

March 8, 2011

The EDA issues an additional $1.7 million in bonds, of which nearly $1.5 are federally subsidized.

April 2011

The school moves into the building.

June 2011

Contractors begin filing construction liens against the property. Some lawsuits follow.

Jan. 18, 2012

The state sends a letter to the school putting it on probation for 90 days.

Jan. 25, 2012

The general contractor, E-Tomic, files demand for arbitration.

May 4, 2012

The Friends file a complaint against the general contractor and subcontractors seeking to consolidate disputes related to the building project. They lay out problems including roof leaks and mold, and raise objections to E-Tomic’s move to take the matter to arbitration.

May 11, 2012

The Education Department extends the school’s probation to Aug 2, 2012.

Oct. 3, 2012

A state judge orders all parties to arbitration.

Oct. 11, 2012

The state extends the school’s probation to Jan. 9, 2013.

Oct. 15, 2012

The school signs a contract with Renaissance School Services, a charter management company. It calls for the school to pay 9 percent of its revenues to the company, as well as the salaries — plus 30 percent — of senior managers who become Renaissance employees.

Feb. 5, 2013

The Friends’ lawyer asks to be removed from the case, saying his firm has not been paid. A judge grants the motion on Feb. 22.

May 7, 2013

The state extends the school’s probation to Oct. 21, 2013.

Oct. 4, 2013

The arbitrator rules in favor of E-Tomic and orders the Friends to pay $582,000. The Friends did not attend the arbitration or request an adjournment; the hearing proceeded in their absence.

Oct. 30, 2013

A state judge confirms the arbitrator’s award and enters final judgment.

October 2014

The federal government receives two tax filings from the Friends — one for 2011, the other for 2013. Erick Torain is the only officer listed. These are the only available tax filings for the Friends.

Nov. 7, 2014

The state extends the school’s probation to March 2, 2015, noting that its charter renewal is coming up.

June 30, 2014

A school employee sends an email to the state saying in part that it has no board or business administrator — all had resigned — and it had no one to sign checks. “Please help!” it concludes.

March 13, 2015

The state sends a letter to the school saying that its charter is not being renewed and that it must cease operations at the end of the school year.

May 15, 2015

The Friends lose their tax-exempt status for not filing returns with the IRS.

June 30, 2015

The school closes.

July-August 2017

The Friends enter into a new lease with College Achieve Public Schools, a charter school management company. The building is subleased to College Achieve Central Charter School.

Aug. 7, 2017

After a lapse, the Friends are reinstated as a business in New Jersey with a new slate of officers; David Berkowitz of Assurance Realty in Newark is listed as president. He replaces Erick Torain as the group’s registered agent in state documents.