School buildings that are paid for with millions of dollars in public money but owned by private groups.

Inflated rents, high interest rates and unexplained costs borne by taxpayers.

And tax dollars used to pay rents that far exceed the debt on some school buildings.

This is the world of charter school real estate in New Jersey.

Where public money can disappear in a maze of intertwined companies.

Where businesses and investors can turn a profit at taxpayer expense.

And where decisions about millions in tax dollars are made privately, with little public input and little to no oversight by multiple state agencies.

More than two decades into the state’s experiment to create charter schools, which were conceived to provide residents with choices and to spur innovation, serious flaws in the design of the system have led to the diversion of millions of dollars in taxpayer money to private companies that control real estate.

Two of the state's largest charter school operators, KIPP New Jersey and Uncommon Schools, have been permitted by the state to monopolize hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid for public school construction, helping them to create networks of privately owned buildings.

And investors positioned themselves to make millions from taxpayers, including real estate entrepreneurs, developers and a range of lenders.

The current situation was born, in some ways, out of necessity.

No system was put in place to help charter operators find and finance school buildings to house and educate tens of thousands of students. In fact, an author of the state's charter school law, which Gov. Christine Todd Whitman signed in 1996, says facilities weren’t addressed to avoid controversy with the state teachers' union and others over the creation of the independent public schools.

A lack of clarity and vagaries in the charter school law ― and what some education experts say is bad policy or no policy at all ― has created a confusing and tangled landscape where transactions are often secret, or buried so deeply in documents that the public has virtually no way of scrutinizing how their tax dollars are being spent.

Private groups that are created to support charter schools ― and own and finance their real estate ― sometimes share board members or officers and lend money to one another. These groups end up owning and controlling facilities leased by the schools, setting rents as they see fit.

“We envisioned paying rent, but we didn’t envision that then there would be the pyramid built upon that.”

“We’re putting a lot of public dollars into the acquisition of assets for private hands,” said Bruce Baker, a Rutgers University professor and a nationally recognized expert on education financing. "All of these crazy, funky, convoluted relationships and kind of specially crafted, third-party organizations are really all a function of just bad policy.”

“We left these organizations to come up with a way to gain access to properties and to retrofit and renovate urban facilities in expensive areas," he added. "And it costs a lot of money, so they had to get creative.”

What that means is that millions of your tax dollars are being siphoned off by private interests to pay for buildings ― often without your knowledge ― that you don't own.

NorthJersey.com and the USA TODAY NETWORK New Jersey reviewed tens of thousands of pages of documents, including lease, property and financing records, state-issued bond sales and audits involving a cross section of charter schools around the state. The findings raise troubling questions about waste, the use of public money, and accountability in a system that receives some $760 million annually from traditional public school districts and educates more than 50,000 students. Another 35,000 are on waiting lists.

Among the findings:

- Charters are using tax dollars to pay rents that far exceed building costs. Some charter schools will pay 15 to 80 percent more in rent over a period of years or decades than is needed to pay off the debt on their buildings. The money flows out of public coffers to private groups created to support the schools.

- Complex transactions hide profits while taxpayers pick up the tab. Financing for one project involved a half-dozen companies, at least as many loans, and two types of tax credits ― resulting in millions of dollars moving from public to private hands with no accountability.

- Charter school operators have exploited a loophole in a federal aid program. They are receiving hundreds of millions of dollars from a program that was meant to spur public school construction but doesn’t require the properties to be owned by the public. Some of the methods used to tap into that aid are now being reviewed by the IRS, which could put some aid in jeopardy.

- Charter schools pay interest rates and fees experts described as very high, damaging and even predatory. Some schools are covering interest-only mortgages with rates that grow each year, swelling in one case to more than 16 percent. For another school building, $25 million in interest would be paid over two decades ― and the $10.5 million initially borrowed for its construction will still be owed. And fees to get out of the deals early can reach millions of dollars.

- Excessive and unexplained fees are hidden in leases and rents. One nonprofit charter school management company rents properties and then leases them to schools, charging as much as 30 percent above what it pays over the lease term and tacking on other costs. In another case, two charter schools are paying rent to cover the purchase of a pair of buildings that increased in price by more than 150 percent, including millions of dollars in fees paid to the seller.

- Charter school properties have been flipped between related companies at inflated prices. One vacant lot was purchased by a private group that supports a charter school. The same day, it sold the land to a subsidiary for nearly six times what it paid, adding nearly $2 million to the debt that taxpayers are covering in rent.

- There is little public scrutiny and lax oversight from multiple state agencies. State education officials don’t review building financing or lease agreements before they are signed. They don’t monitor the associated groups that own real estate for charter schools. And New Jersey has issued more than $800 million in bonds to construct, purchase and renovate charter school buildings without any agency considering who will own them or how much the public will pay in rent.

Dwight Berg, an economist who has worked on charter school facility deals around the country, said New Jersey’s law “doesn’t make any sense” and has “pushed schools away from the smart thing of permanently owning their facilities to leasing."

“I’m sure that’s put a lot of money in private landlords,” said Berg, who has been a financial adviser on KIPP New Jersey projects. He advocates for changing the statute to make it easier for charter schools to borrow and buy property, “and control their own destiny.”

Some charter operators have created networks of private entities ― both for-profit and nonprofit ― to finance and own the real estate that their schools rent with public funds. Many large projects were at least partly funded with hundreds of millions of dollars in federal aid at the direction of Gov. Chris Christie’s administration.

Joseph V. Doria Jr., a former state legislator who was an author of the state's charter school law, said private ownership of charter school buildings creates a “money-making situation” that lawmakers didn’t foresee.

“We envisioned paying rent,” he said, “but we didn’t envision that then there would be the pyramid built upon that.”

State law required an independent evaluation of the charter school program after five years, but Doria, now the dean of education at St. Peter’s University, said it was never done. The administration of Gov. Phil Murphy kicked off a review in October. Under the law, the involvement of private entities in the operation and financial support of charter schools is among a dozen areas to be reviewed.

Charter operators point out that most of those private groups are nonprofits and maintain they are keeping facility costs down. But many details about them are not available to the public. Because support companies are private, it’s often impossible to see routine information, such as interest rates on loans, debt on school facilities or what happens to the money once it leaves the public charter school.

That lack of transparency is compounded by charter operators who have declined to discuss the details of complicated financial deals that leave property in private hands indefinitely.

“We left these organizations to come up with a way to gain access to properties and to retrofit and renovate urban facilities in expensive areas. And it costs a lot of money, so they had to get creative.”

Board members of the private groups — who have included bankers, finance experts and lawyers — also declined to speak with reporters. Among them were Tim Carden, a financier and a member of Gov. Brendan Byrne’s Cabinet, and Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat who was elected to Congress in November. Both were members of multiple boards that rent buildings to one large Newark charter school, TEAM Academy.

Jim Griffin, a former executive director of the Colorado League of Charter Schools, said the public should own school buildings that are funded with taxpayer money.

“It’s public schools, public dollars and public kids,” he said.

Officials at KIPP New Jersey, a regional offshoot of the national KIPP foundation, said they don’t determine in advance what the ownership of a building will be after the debt is paid off.

KIPP New Jersey, which is paid millions of dollars to run TEAM Academy, said it "has determined it is in the best interest of our students and programs to allow the utmost flexibility and consideration of the regulatory parameters at the time to make those decisions when the time comes.”

But that’s not always the case.

TEAM Academy's leaders orchestrated a complicated arrangement more than eight years ago to make sure a $22 million high school building ends up in private hands. However, a federal tax rule requires the building to be owned by the public once the bonds issued to finance it have been repaid. The deal was sanctioned by the New Jersey Redevelopment Authority and by the administration of Newark's mayor, Cory Booker, presidential candidate and New Jersey’s junior U.S. senator.

The building, on Norfolk Street, is owned by a private nonprofit company with ties to the charter school that was created to issue bonds for the project under a rarely used IRS rule. The bonds were purchased by the Friends of TEAM, another group with ties to the charter.

Documents obtained by NorthJersey.com show property transfers that were scripted years in advance to meet an IRS rule. Eight years from now, the building is scheduled to be flipped twice — handed off first to the Redevelopment Authority and then “immediately” transferred to the Friends group.

By then, $30 million in public money would have been invested in a building that is privately owned.

Millions of dollars pass through the Friends group and at least a half-dozen partner companies annually. Recent financial documents show that the Friends group holds nearly $6.7 million in cash, receives millions of dollars in development fees and controls tens of millions more in federal aid and grants.

“We envisioned that charter schools were going to be community-based … to reflect the needs of the community and the parents. They’ve become much more institutional, much more corporate than the original concept of the legislation.”

TEAM Academy hasn’t used the building in years.

For a while it subleased the structure to another charter school for nearly $1 million annually, about three times what it had been paying in rent, passing any earnings to its landlord.

The building is now empty.

But TEAM continues to use taxpayer money to pay its $300,000 annual rent — and as much as $50,000 in landlord and other fees. A sign on a parking lot fence indicates the building will be used by TEAM in the next school year.

The issue of ownership becomes more pressing as charter schools grow — the largest educate thousands of students and plan to expand. That means that the charter school affiliates and support groups will, over time, control more and more property funded by taxpayers.

Doria, the former legislator, said lawmakers never anticipated that many of New Jersey's charter schools would have more than 500 students each. This year, the state expected 30 charter schools to have more than 500 students and 13 to have enrollments exceeding 1,000.

“We didn’t envision organizations like KIPP coming in,” he said. “We envisioned that charter schools were going to be community-based … to reflect the needs of the community and the parents. They’ve become much more institutional, much more corporate than the original concept of the legislation.”

About a third of Newark’s students attend charter schools, and that number is rising. While Booker embraced charters, his successor, Mayor Ras Baraka, has called for a halt to their expansion in the city. Both declined to be interviewed.

TEAM Academy is expected to double in size to nearly 8,000 students within three years. Its private partner groups own five buildings, including a former public school, and other property. TEAM recently purchased its first building, a former Essex County school — but only because public ownership was a requirement of the sale. Bond documents show it intended to finance the purchase with a loan from the Friends group. The Friends group would repay that money by collecting rent from the public charter school, which is funded by taxpayers.

Uncommon Schools, the state’s other large charter operator, is paid millions of dollars to run North Star Academy, which has been approved to expand to 7,300 students by 2020. One of its newest facilities is six stories and 162,000 square feet, and it cost about $69 million. North Star is slated to pay more than $3 million a year to rent it. In all, companies tied to Uncommon own seven buildings that they rent to the school.

Marion P. Thomas Charter School in Newark, which enrolled 1,372 pupils last year, has been approved to expand to 2,250 students by fall 2020. Its supporting organizations own six school buildings, three of which were recently purchased.

Two of those buildings were former Newark public schools.

The Friends of Marion P. Thomas contracted to buy them from the city, but the Friends instead allowed them to be sold to a for-profit developer. The developer then sold them to the Friends — after about two months in the case of one building, and just shy of a year later in the other — for a 150 percent price hike. Fees of almost $6.4 million accounted for much of the increase.

Rent from charter schools, funded by taxpayers, will cover the cost of the sale.

“If the price of pulling a charter is you lose a school facility that taxpayer dollars paid for and have to come up with that much more money to build a new school, it raises a question of too big to fail.”

The group is also in line to buy another former public school building that documents show may be converted to low- or moderate-income housing.

Experts say the movement of school buildings from public to private ownership raises a multitude of issues.

"There’s the ethical problem of buying private property with public dollars, but there’s also the way in which it ties the hands of the policy makers,” said Gordon Lafer, a political economist at the University of Oregon and a former adviser to the U.S. House Committee on Education and Labor.

Those issues are compounded, he said, when a charter school's enrollment grows into the thousands.

“If the price of pulling a charter is you lose a school facility that taxpayer dollars paid for and have to come up with that much more money to build a new school, it raises a question of too big to fail,” he said.

Fewer than 20 of the state's 88 charter schools directly own at least one of their buildings.

Princeton Charter School has owned its facilities since its start in 1997, and now boasts a multi-building campus made possible because parents guaranteed part of the school's first mortgage.

Hope Academy in Asbury Park bought its building in 2016 with the help of a tax-exempt bond issue and a direct loan from the state Economic Development Authority. As a result, its mortgage payments are 40 percent less than the rent it would have been paying to a nonprofit group that previously owned the building.

Some charter operators said they were under the impression that New Jersey charter schools could not own buildings. Others said the state discouraged them from owning property. State education officials say ownership was never prohibited or discouraged.

“I think that there is no reason why we can’t own the school,” said Paul Josephson, board secretary and a former board president of the Princeton Charter School. "And frankly I think it’s the right way, because ultimately public monies are going into the school, and the public monies that go to the school are being used to pay off the loan. And so really, it should be an asset of the school.”

That way, if a charter school that owns its own building closes, the property, like any other asset, would be sold and any excess funds returned to the local school district.

That wouldn’t be the case if the building is owned by a private entity that holds real estate for a charter school.

The state Education Department says it has no oversight over such private groups and doesn’t “regulate privately owned buildings if the charter school closes.”

Most charter schools rent, whether from unrelated commercial landlords, nonprofit groups or other private entities created to support them or own real estate.

Many look to churches. The Catholic Church, often through its local dioceses, is the largest landlord to charter schools in the state, and the public often pays to refurbish aging and vacant church buildings.

There are charter schools paying rent to a college, a medical group, a luxury building owner and developers who have renovated properties and strike long-term, multimillion-dollar leases with schools.

To be sure, not all agreements are unfair to the public charter schools.

But in its review, NorthJersey.com saw questionable fees, interest rates and other provisions in contracts.

Some contracts were vague. A few didn’t specify the amount of rent to be paid. Some included provisions preventing private charter school management companies from being fired without the landlord’s consent. And one gives a landlord the opportunity to collect more from the school if its revenues rise.

One lease puts the cost of monitoring for environmental carcinogens on the charter school that rents the property. Another included a $350,000 charge — up front — for a nonrefundable purchase option on a Catholic Church-owned building.

A subsidiary of Uncommon Schools donated millions to its North Star Academy Charter School in 2017. But a lease signed by the charter required it to give that cash to another subsidiary that was in the process of renovating a building it owns and now leases to North Star.

Some charter schools sublease facilities from charter school managers, who may tack on other costs in the process.

College Achieve Public Charter Schools Inc. rents buildings and then turns around and leases them to the three charter schools that it manages with locations in Paterson, Asbury Park, Plainfield and North Plainfield.

Rents in some subleases provided were 10 to 30 percent above what College Achieve was scheduled to pay; the nonprofit also offers maintenance at a 20 percent markup.

At the same time, College Achieve receives more than 14 percent of each school’s revenues as a management fee — an estimated $3.5 million this school year. And documents show that College Achieve, and not the public charter school, holds the purchase option for at least two buildings.

It adds up. A 10 percent increase written into the sublease for one facility, for example, will mean nearly $40,000 more per year in public money going to the rent. Another sublease includes a markup in rent of more than $250,000 over four years. Both leases included “start-up” fees of $100,000 or more that the management company declined to discuss.

Key details are lacking in publicly available documents.

On another College Achieve property in North Plainfield, neither the lease nor the sublease provided includes the rent. The sublease notes an extra $48,000 a year in fees that College Achieve declined to explain. And College Achieve also would not say if it — or the public charter school — would cover a $500,000 annual “cash collateral” payment that records show begin next school year.

Rent for the charter school subleasing its Paterson location is scheduled to be boosted by almost 80 percent next school year, to more than $1 million, documents show. The new building owner has taken out loans to repay debt and cover the costs of continued renovations. But there is no way for the public to know what College Achieve pays in rent to justify the price hike — because it won’t provide an amended lease that property records show was struck this year.

Many pacts that charter schools have struck with associated groups or commercial landlords call for the school to pick up property taxes. One school has paid as much as $330,000 annually. Traditional public schools, by contrast, don't pay property taxes on the buildings they own.

Contracts often call for charter schools to cover the cost of building repairs and any upgrades needed to get a facility in working order. A Trenton charter pumped $400,000 into a church-owned building that its board president termed a “nightmare.” The charter school left that facility — and its investment — for a pricey new building within three years before being closed by the state last year.

Elsewhere, charter school affiliates have created elaborate financing strategies that combine state-issued bonds, federal aid and a mix of tax credit programs that draw in banks and other investors.

“These convoluted transactions scream at me,” said Griffin, the charter school advocate from Colorado. “When we don’t have clear charter financing mechanisms, we wind up with goofy, bastardized financing.”

One of the most complex of these transactions, orchestrated by KIPP New Jersey, involves the purchase and renovation of a former Newark public school building.

KIPP's TEAM Academy Charter School is scheduled to pay 80 percent more in rent — money provided by taxpayers — than is needed to cover the dept on the property. The building's owner, identified in tax records and other documents as Pinkhulahoop1 LLC, would pay out close to $16 million in dividends over 30 years to private companies created to support the charter school.

KIPP officials said that the rent is reasonable and that millions of dollars are donated back to the school.

Tax records show the Friends of TEAM has taken in more than $27 million in grants and donations since 2010; the school has received just over a third of that money.

A central issue is a state law and regulations that even some charter operators describe as both confusing and burdensome — and open to interpretation.

The state provides no start-up or facilities funding for charters and puts limits on the debt the schools can carry — rules that some say effectively prevents schools from owning their own buildings. Any debt carried for more than 12 months must be fully secured by property or other assets, and are "non-recourse to the charter school."

That means that if the school should default a lender can seize only the property.

Charter schools can't use state and local dollars to build a new school — a provision clarified in 2017 to mean a completely new building. Additions and renovations are allowed.

They can’t issue bonds and raise taxes like traditional public schools can. And unlike some other states, New Jersey offers no clear mechanism for a charter to access unused space in the traditional public schools: One study shows that 18 states and the District of Columbia require surplus space to be offered to charter schools first before it is leased or sold to other buyers.

“All facility projects must come out of the charter school’s operating budget, diverting necessary funds from classroom instruction,” KIPP New Jersey said in a statement.

The law requires districts to send charter schools 90 percent of what they receive in local taxes and in some state aid for each student.

But charter schools on average receive only about 73 cents on the dollar in local and state aid compared with traditional public schools, according to the New Jersey Charter Schools Association.

It can be much lower. For example, Asbury Park charter schools received 42 percent of district per-pupil funding in the 2017-18 school year while those in Jersey City got 60 percent, according to the association. Much of the disparity is due to so-called “adjustment aid” that some districts receive.

New Jersey initially approves charter schools for four years and they subsequently come up for renewal every five, a turnoff for many lenders and landlords. Some charter school support organizations say bankers often require that the loans go to private groups that own the school buildings and carry the debt.

So, private groups own the property, set the rent and pay off debt with public money from the charter school. Construction by — or on behalf of — charters isn't coordinated with local school districts.

Unlike New Jersey, a number of states offer charter schools help with facilities, including direct funding, loan guarantees and reimbursement for lease payments.

“All facility projects must come out of the charter school’s operating budget, diverting necessary funds from classroom instruction.”

Still, the lack of readily available funding for facilities is a nationwide problem — one that can prevent charters from opening or expanding.

Private ownership of charter school buildings is not uncommon in other parts of the country. Some experts believe it has as much to do with fears about traditional public schools laying claim to the buildings as it does with local laws and financing issues.

“I think there was a failure to anticipate private entities taking advantage,” said Preston Green, a professor of education leadership and law at the University of Connecticut.

He said the lack of guidelines for those companies opened the way to potential abuses — drawing a comparison to the lax regulation of financial markets that led to the subprime mortgage crisis a decade ago.

“There has to be more regulation to guard against the types of abuses that we’re now seeing," he said.

No state agency appears to be looking closely at any of these transactions.

The state Education Department says it has a staff of five in the office responsible for overseeing charter schools, which has had six directors in the last 10 years. The same office oversees a network of “renaissance schools" in Camden that operate under separate rules than charters. They receive more funding, are allowed to use state funds to construct new buildings and are approved by the city’s school district.

Regulations don't limit how much is spent on charter school facilities, state education officials said.

The Education Department said in a statement that it does not have authority over “contracts between the [charter school] boards and private entities.” It doesn’t have the authority to review “financing or lease agreements before they are signed,” or to “receive management agreements for all charter schools” that contract with a management company. It doesn’t approve or review charter school projects or long-range facilities plans.

And the department said it “doesn’t oversee private related companies." The department noted that it is responsible for “ensuring the school is fiscally sound and providing a quality educational option for students.” It receives schools’ audits and budgets, and state regulations call for the education commissioner to ensure that charter schools spend about the same percentage of their funds “in the classroom” as traditional public schools.

The department said it looks at rent as a budget line item “when assessing the financial health of the school.” But it does not examine those rents as they relate to the debts on the buildings.

And when schools sublease buildings, the state doesn’t look at what a school’s landlord pays for the property.

James Goenner, a charter school advocate, said he was “blessed” to have 30 staff members when he headed an office in Michigan overseeing 60 charter schools — about a third fewer than New Jersey — with 30,000 students. He said the capacity of state agencies and other offices to adequately oversee charters has been a nationwide issue.

While public-private partnerships can help charter schools obtain facilities, he said, they also need to be monitored. The office that Goenner led for 12 years until 2010 had an answer ready when private companies refused to open their books.

“We would smile at that and say, ‘We can understand your position,'" said Goenner, who now leads the National Charter Schools Institute. “‘You could choose to be cooperative or you could choose not to work with this school.' We used our influence in a proactive way.”

“I think that there is no reason why we can’t own the school. And frankly I think it’s the right way, because ultimately public monies are going into the school, and the public monies that go to the school are being used to pay off the loan. And so, really, it should be an asset of the school.”

The New Jersey state agency that helps charters finance construction said it doesn’t consider what schools pay in rent or who owns the buildings. The Economic Development Authority has issued more than $800 million in bonds for charters and other nontraditional schools. It lends cash from the sale of the bonds, but a former director of the agency, Timothy Lizura, emphasized that the money comes from the purchaser with no state funds involved.

Yet more than half of those bonds were issued with federal subsidies attached.

Lizura said the agency is just “a pass-through” for the loans, which is why it doesn’t thoroughly examine the details of these transactions, including the use of public money to repay the loans.

“As the conduit issuer, we wouldn’t look at those things,” Lizura said.

He said the authority “doesn’t work too much” with the state Education Department other than to confirm that charter schools are in good standing.

Yet the Economic Development Authority issued more than $10 million in largely tax-exempt bonds two years ago for the Jersey City Community Charter School while it was on probation — money that was used to refinance debt on buildings owned by the school, to pay operating expenses and to buy classroom supplies and equipment.

The school was taken off probation in early 2017. Months later, the bonds were downgraded to junk status by a Wall Street ratings agency that described its overall outlook on the bonds as “negative.” It cited, in part, “management’s inability to accurately budget and forecast enrollment.”

The EDA also issued $10 million in bonds in 2013 to benefit the troubled Lady Liberty Charter School in Newark, a year after it came off probation.

The arrangement saw a nonprofit unrelated to the charter school create a company to act as the borrower and construct an addition to a church-owned building. Lady Liberty subleased the facility, and its rent payments covered the debt on the bonds, the lease payments to the church, plus an annual management fee that was scheduled to climb to $40,000.

Three months after the bonds were issued, the state expressed concerns about the school’s academic performance. Later that year, the school was found to have failed to follow rules related to its spending of federal and state money in a report issued by the Education Department’s Office of Fiscal Accountability and Compliance.

In June 2014, Lady Liberty was back on probation, where it remained until the state shut it down last year.

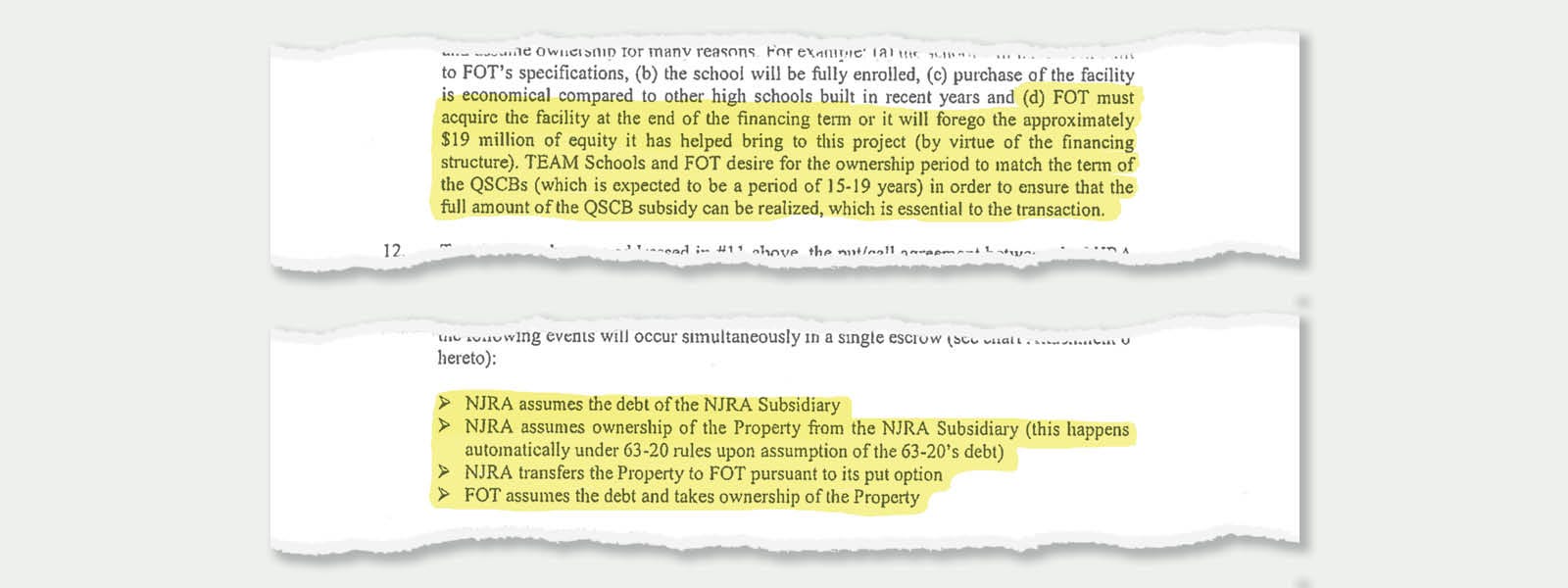

Eight years from now, a private company that owns a Newark charter school building plans to give it to the state. But public ownership of the building, constructed using millions of dollars in taxpayer money, would be brief.

As part of back-to-back transfers arranged years in advance, documents show that a state agency has agreed to “immediately” transfer ownership of the building to another private company that was created to support the charter school.

By that time, taxpayers would have pumped tens of millions of dollars into the building. And the public charter school would continue to pay rent — an amount that would exceed $1 million annually by 2027.

It’s all part of a series of transactions worked out more than eight years ago to briefly meet a tax requirement that the public take ownership of the building.

The people who ran TEAM Academy Charter School — which is part of KIPP, one of the country’s largest charter school networks — approached the New Jersey Redevelopment Authority with a plan. They proposed creating a company called NCA Facility Inc. as a special kind of private nonprofit corporation, taking advantage of a rarely used IRS rule. The private nonprofit would have the authority to issue millions of dollars in bonds on behalf of the public to be used to build a high school for TEAM on Norfolk Street called Newark Collegiate Academy.

The IRS rule in question, however, comes with a provision: Buildings constructed with the funds are required to be owned by the public once the debt on the bonds issued for the project is paid off.

When the bonds used to finance the project are set to be retired, the Redevelopment Authority will take control of the building to comply with tax rules, according to documents obtained through public records requests.

However, the documents show that the authority would immediately transfer ownership of the building to the Friends of TEAM, a private nonprofit group that supports the charter school in real estate transactions.

The Friends group purchased the bonds in 2011 as a loan to NCA Facility to construct the building. The redevelopment authority agreed to take on the debt decades later and repay it by giving the building to the Friends.

The authority would act as a pass-through to erase tens of millions of dollars in debt that TEAM Academy's support groups essentially owe to themselves.

By then, the federal government would have paid more than $23 million in interest on the project as part of a school construction aid program. State and local taxpayers would have contributed millions more in rent, bringing the public’s total investment to around $30 million.

The administration of Cory Booker, Newark's mayor at the time and now a U.S. senator, encouraged the deal and signed off on the transfer of the property to the private Friends group. The city also recommended, with Booker’s prodding, that millions of dollars in federally subsidized bonds meant for traditional public schools in Newark be given to charter schools instead.

More than $21 million in bonds meant for the district were eventually used in the Newark Collegiate Academy project, according to documents.

A total of $53 million in bonds earmarked for Newark all went to fund privately owned charter school projects in the city — with the federal government picking up the interest as a subsidy.

Booker did not respond to a request to discuss the NCA deal, but he issued a statement saying his intent was to improve education for Newark’s children. He said that “the federal financing made available would have been lost to Newark” if the bonds weren’t issued and that “the decision was made by multiple government agencies to ensure it went towards strengthening our public school system.”

A state Treasury Department report indicates that the city would have been required under some circumstances to give unissued bonds to the state to be redistributed. Booker did not address the question of the school building’s ownership. A former member of his administration said no one at the time considered who would own the property.

TEAM Academy has since moved Newark Collegiate Academy out of the publicly funded building, which has continued to generate income for its private owner.

The high school now operates out of another building that was built using $40 million in state-issued bonds. For the last two years, TEAM sublet the Norfolk Street building to another charter school, North Star Academy, for $1 million annually — about three times what TEAM had been paying in rent.

But TEAM didn’t get to keep any of that money. All of it was passed on to the property’s private owner, NCA Facility.

Another charter school briefly rented the building last year, but it’s been vacant since November.

For now, TEAM Academy continues to pay $350,000 in annual rent on an empty building.

Cory Booker pushes a redevelopment deal

In a March 2010 email to the Newark city clerk, Booker requested that the City Council consider a resolution naming the Friends of TEAM as the exclusive redeveloper of the Norfolk Street property, adding that “this item is time sensitive.” The measure passed unanimously two weeks later.

A TEAM administrator explained plans to finance the $22 million Norfolk Street project in a letter to the state Redevelopment Authority dated that October.

Ryan Hill, then TEAM Academy’s CEO, now leads KIPP New Jersey, which was formed in 2013 to manage TEAM and other nontraditional schools in New Jersey. He told the authority in the letter that the city had targeted the site for residential redevelopment, but a weak economy prompted a change of plans.

The owner of the land was a real estate entrepreneur, David Berkowitz, who agreed to sell it to a company related to TEAM. Berkowitz and a partner, Ian Mount, created a new company to manage the charter school project.

“We understand this structure might be unfamiliar.”

The deal centers around a relatively obscure IRS rule that allows some nonprofits to issue bonds on behalf of government agencies. The IRS requires such corporations to be “controlled” by a government agency, and for the bonds they issue to be for a “public purpose.” The nonprofits are known as 63-20 corporations, for the IRS rule that applies to them.

Hill asked the authority to create such a company — NCA Facility — to issue bonds on the authority’s behalf to help finance the Norfolk Street project.

Once the bonds have been paid off, IRS rules say, the property must be transferred to the government agency that approved them.

“We understand this structure might be unfamiliar,” Hill wrote.

Bond documents show that NCA Facility later issued more than $21 million in federally subsidized bonds on behalf of the Redevelopment Authority. The state Economic Development Authority issued an additional $6.7 million in the same type of bonds to be used in the transaction.

Hill outlined in the letter how the debt on the building would disappear after two quick transfers.

NCA Facility would use money from the bond sale to construct the Norfolk Street building and to own it. But the Redevelopment Authority had to take “nominal ownership” of it at some point because of “tax requirements,” Hill wrote.

“These convoluted transactions scream at me. When we don’t have clear charter financing mechanisms, we wind up with goofy, bastardized financing.”

By then, documents show, NCA Facility would owe more than $28 million to the Friends group, which borrowed from banks to purchase the bonds.

But tax rules allow the authority to take ownership before the debt is paid — and that’s what it agreed to do, taking on NCA Facility's debt to the Friends as part of the first building transfer. In the last step, Hill told the authority, the Friends group “assumes the debt and takes ownership of the property.”

The building transfer would be considered payment of the outstanding debt that NCA Facility owed to the Friends.

KIPP New Jersey declined to discuss the NCA deal but issued a statement acknowledging that the Redevelopment Authority would take ownership and then “satisfy the bond debt” by transferring the building to the Friends “in lieu of cash repayment.” The transactions, the statement said, followed “applicable federal tax law” and involved “unrelated parties.”

The companies involved are considered separate, but they have ties to one another.

Tim Carden, NCA Facility’s president, also sits on the Friends’ board. He declined to comment when reached by phone and did not respond to messages.

After the bond debt is erased, documents show, the Friends group may add new debt to the building to repay new loans with the public charter school’s rent.

“We were focused on the school being built. I don’t recall any discussion about changing the ownership of the building.”

A school building to pass (briefly) through public hands

The quick transfer of the building was mentioned in multiple documents.

Leslie Anderson, the executive director of the state Redevelopment Authority, told the board’s agency in a memo that the authority would take control of the building and “immediately transfer ownership of the school facility to Friends of Team.”

Booker’s administration also approved the building being “immediately” transferred to the Friends in a redevelopment agreement signed by Stefan Pryor, then Newark’s director of housing and economic development.

Timothy Lizura, who was president of the Economic Development Authority at the time, said his agency played only a small part in financing the project. He directed questions about the deal to the redevelopment authority.

Anderson, the head of that agency, declined to comment. Pryor, who later became Connecticut’s education commissioner and is now Rhode Island’s secretary of commerce, did not respond to requests to be interviewed.

A former member of the Booker administration, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said the primary concern driving the construction of the Norfolk Street building was the need to provide educational opportunities for Newark’s children. The issue of ownership, he said, wasn’t considered.

"We were focused on the school being built,” he said. “I don’t recall any discussion about changing the ownership of the building.”

The transaction seemed simple enough on its face. The Newark Public School District sold a run-down elementary school to a private, for-profit group for use by a local charter school.

But the purchase and rehabilitation of the century-old building on 18th Avenue was financed with money raised through a complex series of transactions fueled by federal and local tax dollars. The cost topped $36 million before it opened to charter school students in 2014.

The company that runs the charter school said the deal saved money and keeps rent “as low as possible.”

However, the rent that TEAM Academy Charter School will pay over the next three decades — all of which comes from state and local taxpayers — will be 80 percent more than is needed to pay the debt held by the for-profit company that owns the building.

Over that time, tens of millions of dollars will fall to investors and other interrelated nonprofit groups as the rent gradually climbs to $3.8 million annually.

It’s perhaps one of the starkest examples of how tax dollars that charter schools spend on facilities can exceed the costs borne by private groups that support them by owning real estate and entering into financial transactions on their behalf.

Some experts say the money a school pays over and above what is needed to cover the debt on its building is returned to it in many cases.

“What I have seen in the past is that excess often gets round-tripped back to the school,” said David Scheck, a financial consultant and a former president of New Jersey Community Capital, a nonprofit that lends money for charter school projects. “It’s rent that’s paid over and above the amount of debt service that’s needed, and then at the end of the year … that excess gets contributed back into the school.”

But in most cases, there is no guarantee that any excess funds paid will be returned or that rent payments will end when the debt is paid.

Some charter schools pay only enough to repay the debt on their buildings. Others pay hundreds of thousands more every year in rent. For the 18th Avenue school, that figure is more than $400,000 a year and is scheduled to reach more than $1 million annually by 2032.

It’s just one instance where charter schools are paying more in rent than is needed to cover their building debt.

“What I have seen in the past is that excess often gets round-tripped back to the school. It’s rent that’s paid over and above the amount of debt service that’s needed, and then at the end of the year … that excess gets contributed back into the school.”

NorthJersey.com and the USA TODAY NETWORK New Jersey found the following:

- North Star Academy will pay rent that’s 15 percent more than is needed to cover the debt on its newest building in Newark according to documents. But an analysis of debt and rent schedules shows lease payments would exceed by 50 percent what is needed to cover the debt on the $24.6 million in bonds that the state issued to finance its construction. An affiliate of the company that manages the school lent $2.8 million to a related company that owns the building. That amount appears to be too small to make up the difference, unless the interest rate is extraordinarily high or there’s another loan that is not mentioned in the bond documents. The school’s operator declined to explain.

- In Camden, a nonprofit charges a charter school $3.3 million to rent five buildings — an estimated $1.5 million more than is needed to cover the annual debt, a calculation based on a review of bond documents and partial information provided by the landlord on another loan. Camden’s Charter School Network, which owns the buildings, calls the rent “commercially reasonable and below fair market value,” and said any payment “in excess” of the amount needed to pay the debt “is returned to the schools in one way or another.” But the group’s tax records do not show any grants to the charter school; the school’s records do not show that it has received any money back. The network’s director said the company “continues to acquire neighboring properties” for the charter school’s use and spent $335,000 on building upgrades "this summer alone." Records show it paid more than $500,000 for property last year. The school also pays the landlord $1.1 million a year for maintenance.

- In Newark, the rent that TEAM Academy pays each year to use buildings on Ashland Street and Custer Avenue exceeds by 20 percent the annual debt on $21 million borrowed to purchase and upgrade those facilities. The rent is $1.5 million a year; the annual debt payments total about $1.25 million. Documents show the property owner — a nonprofit named Ashland Schools Inc. — keeps the excess and “at its sole discretion” may donate that money to TEAM; to Friends of TEAM, a group that supports the school in real estate transactions; or to “other entities,” provided that any required repairs have been funded. Records show TEAM has received a $263,000 refund, which is equivalent to a year of excess rent. But it paid more than $1 million in “additional rent” in 2017 and 2018.

- In Paterson, a charter school pays $2.63 million in rent annually to a subsidiary of a nonprofit for two buildings. That’s 30 percent more than the annual debt payment on more than $30 million in bonds that the state issued to finance the purchase and renovation of one of of the structures. The Paterson Charter School for Science and Technology had been paying $400,000 more than the annual debt payments; a lease amendment signed in 2017 boosted its rent to nearly $600,000 more than is needed to cover the debt. Leases say the difference between the rent and the debt service and other costs is considered a landlord’s fee, and a school official said it was that portion that was increased. The landlord, a subsidiary of Apple Educational Services, said it maintains the buildings at considerable expense, and that it spent $360,000 last year just on new air conditioning. But the school now must also reimburse the landlord for any costs associated with monitoring for environmental issues at one of the buildings.

In many of the documents reviewed, there is no indication that ownership of the buildings will ever shift from the private entities to the public charter schools.

And when there is, there can be loopholes that keep them in private hands.

In the case of the Paterson school, the recent changes to its leases boosting the rent also added a provision permitting the charter to purchase each building for $1 when the bond debt is paid off in 2044. But the lease allows the charter to designate a third party that supports the school to receive title to the property.

By then, the charter school would have paid at least $15 million more than the debt.

In Camden, two buildings that were owned by charter schools are now privately held, having been transferred to a private group for $1 each.

That group, Camden’s Charter School Network, said lenders required it to own the two properties in order to get financing for new projects. The charter schools that had owned the buildings merged into a single school. That school now rents those buildings — and three others — while continuing to repay federal bonds related to one of them.

A complex deal leaves taxpayers on the hook

Of the transactions reviewed, one of the most expensive for taxpayers — and by far the most complex — involves the 18th Avenue school in Newark that TEAM Academy rents.

The building was purchased from the Newark school district in 2013 for $4.3 million. The sale and improvements were financed through a series of transactions involving multiple entities, including five private companies that support the charter school.

The property is owned by Pinkhulahoop1 LLC, which supports TEAM and was created as a for-profit company to take advantage of a federal tax credit.

Documents show that Pinkhulahoop1 is scheduled to pay at least $47.5 million over 30 years to cover the building’s debt.

The public charter school, however, will pay $84.3 million in renpt over that period, according to an analysis of rent schedules in lease documents.

Taxpayers will also kick in an estimated $40 million in federal aid for the building project. An additional $8 million in federal tax credits will go to one of the lenders.

In all, about $130 million in public money is scheduled to be pumped into the project.

All that cash supports a complicated financial deal that includes multiple loans and tax credits, and millions of additional dollars in fees and other expenses that are driving up costs for the school. Much of that will be distributed to TEAM’s support groups and other investors in fees and interest payments.

Most of the loans in the transaction have low interest rates, but other payments built into it increase the costs, which are funded by the public charter school's school's rent.

Friends of TEAM, for example, will receive more than $5 million in development fees and another $5 million in management fees and other distributions, documents show.

And two affiliates are getting back close to $16 million on a $1 million investment. Documents show the money is being distributed as "dividends."

Experts say this is an unusual arrangement.

"I've done this 25 years and I've never heard the word ‘dividends’ mentioned once,” Jim Griffin, a charter school expert and a former executive director of the Colorado League of Charter Schools, said after the arrangement was described to him.

Where does the money go?

Most of those dividends go to Kingston Educational Holdings 1, an entity created to help acquire property for TEAM’s use. Kingston will take in an additional $12 million in interest from two loans it made as part of the transaction.

It is not known how that money will be used.

Two of Kingston’s board members at the time, Dan Adan, who has also served on TEAM’s board, and Tim Carden, who serves on the board of Friends of TEAM, declined to speak with reporters.

“I can attest that our real estate and associated financing transactions were structured and completed with one goal in mind: to provide the best possible facilities for our students at the most efficient cost,” Adan said in an email. “There is no doubt that these facilities and associated improvements have benefited both the students and the Newark community.”

“I think there was a failure to anticipate private entities taking advantage.”

Mikie Sherrill, who served on Kingston’s board for about four years before she was elected in November to represent the state’s 11th District in Congress as a Democrat, also would not speak with reporters and did not answer questions that her staff requested be submitted in writing. Sherrill and Adan also served on the board of Ashland Schools Inc., which owns two buildings used by TEAM but was not part of the 18th Avenue transaction.

Officials at KIPP New Jersey, which is paid to run TEAM and is one of the state’s largest operators of charter schools, also declined to discuss the financing on the 18th Avenue school. But they said in a statement that the charter school is paying “a reasonable sum” to rent “a state-of-the-art facility.”

TEAM now pays nearly $2 million annually in rent on the building and is responsible for its upkeep. The public charter school also picks up about $330,000 in annual property taxes because Pinkhulahoop1, which owns the property, was created as a for-profit company to get the benefit of federal tax credits.

KIPP officials said federal tax credits helped to lower the cost of the building and more than made up for the property taxes paid by the school.

But Pinkhulahoop1’s for-profit status means it’s scheduled to pay more than $13 million in federal taxes through 2045.

Tax credits used in the project were passed to a bank in exchange for low-interest loans. Financial experts said that once the credits are used by the bank, loans related to the project could be refinanced, freeing up millions of dollars that could lower rents or be used for some other purpose. Documents indicate that the rent continues to rise.

“I can attest that our real estate and associated financing transactions were structured and completed with one goal in mind: to provide the best possible facilities for our students at the most efficient cost. There is no doubt that these facilities and associated improvements have benefited both the students and the Newark community.”

KIPP officials said that any excess rent paid by TEAM is used to “pay creditors, establish required reserves or is returned to the schools in subsidies.” Their landlords, they said, do not keep excess cash from rents.

“To the contrary, more than $10 million has gone back into our educational programming since 2009,” the statement said.

KIPP officials did not elaborate. And no documents link the excess rent to payments made to the school.

Financial records show the Friends of TEAM gave the school more than $10 million during that period. During the same time, the Friends received more than $27 million in grants — almost three times what it gave to the school.

Email: rimbach@northjersey.com and koloff@northjersey.com

The story has been updated to reflect that North Star Academy's building in Newark is open.

Timeline: KIPP TEAM Academy Charter School, Newark Collegiate Academy

Almost a decade ago, officials at TEAM Academy Charter School approached a New Jersey state agency with a proposal. TEAM would create a company called NCA Facility Inc. as a private nonprofit corporation to issue millions of dollars in bonds — funding that was part of a federal school construction program and originally earmarked for Newark’s traditional public schools — to build a charter high school for TEAM on Norfolk Street called Newark Collegiate Academy. The nonprofit would construct the building and own it until the bonds mature in 2027. Then, to meet tax rules, it would give the building to the state agency, which would turn around and give it to another private group with ties to the school called the Friends of TEAM. Here’s how the arrangement came together: